By Roland Murphy for AZBEX

The City of Chandler probably didn’t expect to be a trendsetter when it passed its ordinance restricting data center development in late 2022. After all, there were only four projects planned there at the time, and other cities had much more available area and better overall appeal.

Chandler’s restrictions included limiting data centers to only areas with planned area developments in place, establishing data centers as an ancillary use, requiring noise studies and mitigation measures, increasing notification requirements and other mandates to make the developments more “harmonious” with residential communities.

Then, last December, Phoenix advanced a proposed ordinance with many of the same restrictions. In May, Mayor Kate Gallego, in her State of the City address, derided data centers for what she characterized as unappealing aesthetics, impacts on walkability and neighborhood vitality, high energy demand and perceived impacts on water resources. (AZBEX, May 21)

Phoenix’s proposal had an exceptionally accelerated timeline, pressing for a full City Council vote to come this week. The City’s Village Planning Committees have balked at the pace, with nine of the 14 Committees voting on the issue passing their recommendations with a request for a 60–90-day period for stakeholder input to redraft the ordinance before Council takes a final vote. (AZBEX, June 10)

Last week, it was reported Tempe and Mesa were considering their own zoning updates with similar restrictions.

All this comes about as metro Phoenix has developed into, depending on what study one examines, the fourth or fifth leading market for data center development in the United States.

The Logistical Debate Points

There is no denying the scale and scope of Arizona data center development have presented exceptional challenges, particularly on the power development front. At various BEX events, representatives from APS and SRP have focused on the extreme difficulties their companies face in anticipating and supplying power to meet the demand created by data center and advanced manufacturing users.

Around the country, several companies are working to develop safe micro-nuclear power generation solutions, which worries a portion of the public that still thinks nuclear equates to Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima, and utilities are racing to find innovative solutions to increase capacity.

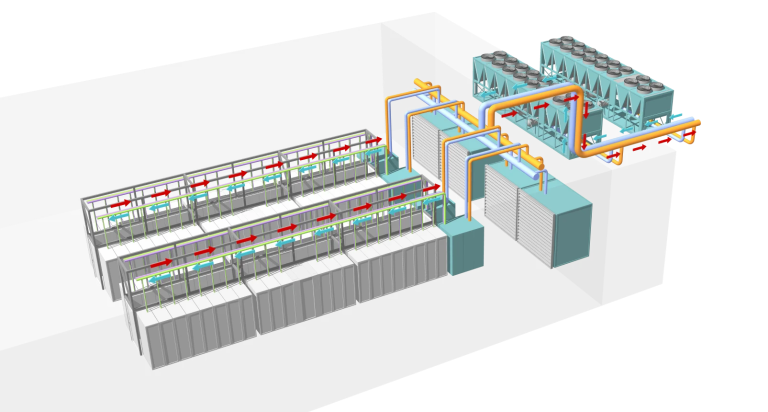

Water usage, while once a primary environmental and technological roadblock for data center expansion, is largely a solved issue. Data centers are high-demand users, but modern designs now almost universally incorporate a closed-loop cooling water approach, which has a relatively negligible impact once the initial water is sourced.

Mayor Gallego and others have criticized data centers as providing comparatively few jobs. While certainly providing fewer jobs than, say, a factory, those jobs still tend to pay exceptionally well. Whether a city benefits more from 120 highly paid workers in a data center at $65K/year or 250 workers at $30K/year in a retail center is a discussion worth having.

The true elephant in the room, however, has parked its bulk between two distinct and divisive definitions of what constitutes positive development. One side examines investment and economics. The other focuses on interconnectedness, equity and community. Both have advantages and disadvantages.

The Political Split

The more restrictive data center camp is primarily, but certainly not exclusively, comprised of those on the political left and reflects that side’s platform planks when it comes to development policy. Among those issues are walkability and promotion of alternative transit, along with neighborhood retail and commercial.

The purported upsides include greater immediate access to goods and services for a greater percentage of the population, a greater diversity of development types, and the creation of new and vitalization of existing neighborhoods and groups.

The pro-data center side leans, but is (again) not exclusively, right-leaning, with a focus on development at the largest possible scale across the widest range of types, with the theory that a rising tide lifts all boats and social improvements follow economic ones.

The Phoenix Mayor and City Council currently lean left, as does Tempe. For several years, both cities have actively undertaken new development policies encouraging the types of development described above.

Phoenix, for example, has implemented a Walkable Urban Code and Transit-Oriented Development standards. Tempe has focused extensively on its own transit-oriented guidelines and other similarly community development-focused standards.

Mesa has traditionally leaned right, although that position has moderated in recent years with population shifts. Mesa’s potential shift on data center policy is at least partially attributable to its own track record in recent years.

Mesa Leads Valley Data Center Development

Unlike Phoenix and Tempe, Mesa has not seen a comparable boom in private development following light rail. While the city has added roughly 36,000 new residents since 2015, and its residential development growth has generally tracked, its retail and lifestyle development has not kept pace with other cities. Officials have repeatedly decried the lack of quality and diversity, and the City’s sales tax revenue has ranked third-lowest among the 11 Valley cities (AZBEX; Sept. 18, 2024)

Redevelopment of existing areas, such as the Fiesta District and the non-core sections of Downtown, has suffered starts and stops for decades. The City has repeatedly trumpeted plans and investments to drum up development enthusiasm, only to go silent when those plans have faltered.

What has allowed Mesa to prosper to the extent it has is available land and the boom in warehouse and data center development. Not including master plans and canceled projects, the DATABEX project database, shows 99 warehouse/manufacturing projects in Mesa with a total construction valuation of nearly $6.79B and a total of more than 50MSF since mid-2016. Most of these projects are in warehouses and logistics.

Over the same time period, Mesa has established itself as the clear leader in data center development, with a total of 18 projects, again not including master plans or cancellations. These data center developments have an estimated construction valuation total of more than $8.36B and more than 14MSF of space.

For comparison, Goodyear is next in the DATABEX data center project count at 14, followed by Phoenix with 12. It is worth noting there are no data center developments planned in Tempe. Since Tempe is entirely surrounded by other cities, it has relied on redevelopment of existing space and the implementation of more verticality to deliver project space in recent years. The likelihood of a developer proposing a data center project in Tempe is remote compared to the advantages other cities provide for that type of facility.

Mesa has, however, been painted into a development corner. As noted above, warehouses and data centers do not provide high volumes of jobs, particularly relative to the space they occupy. City leaders have been trying to figure out how to diversify the types of large scale developments coming to town for years.

This need is particularly pressing in the 85212 ZIP Code area, which is loosely bounded by Meridian/Ironwood roads in the east, Power/Recker roads in the west, Germann Road in the south and Guadalupe Road in the north. All the city’s data centers and more than 75% of its warehouse/manufacturing developments since 2016 have been 85212.

At the same time, 85212 has seen its population swell from a little more than 40,000 residents in 2020 to an estimate of almost 52,500 in 2025, and public officials universally want to generate well-paying jobs near growing populations.

There is also the fact that the warehouse rush in recent years has led to oversupply in some logistics segments. The pace of new development is generally slowing, and lease-up times are growing.

The same cannot be said of data centers, which continue to experience a demand surge with the growth of artificial intelligence and other advanced computing applications. One has to wonder if some leaders are not picking an ill-advised target or painting with too broad a brush across all aspects of Industrial sector development types.

The Economic Development Argument

Not surprisingly, business and economic development leaders have come out en masse against the proposed new data center zoning and permit restrictions.

In a May 18 opinion piece, Arizona Commerce Authority CEO and President Sandra Watson said, “To be successful, we must be open to all opportunities in the AI sector while continuing to pursue smart, strategic growth.

“Data centers represent the backbone of AI development and offer a significant economic opportunity for Arizona.”

Watson also addressed the power and water issues, praising data centers for their use of recycled water and other innovations to keep their usage impacts as low as possible.

In touting the benefits of data centers in the overall Arizona economy, she wrote, “The capital investments made by data centers stimulate local supply chains, benefiting suppliers, contractors, and construction workers. These projects not only drive immediate economic growth but establish long-term economic stability by attracting further technology investments and development opportunities.”

Arizona Chamber of Commerce & Industry President and CEO Danny Seiden also wrote an opinion piece in support of data centers in which he took cities to task for putting out “not welcome signs” because of data centers’ space and energy needs and comparatively low job generation and said, “They could not be more wrongheaded.”

Seiden wrote, “While data centers may not employ thousands of people onsite, their impact ripples far beyond their walls. Each center supports a network of electricians, engineers, construction workers, IT professionals, security teams, and more. Cities that reject these projects or demonize them do so at their own peril—capital projects like this help bring needed tax dollars for schools, police, and fire. And importantly, data centers enable every other job in a digital economy—from fintech startups and defense contractors to e-commerce platforms and healthcare providers.”

He later said, “The presence of these centers also signals something else: Arizona is a player in the global technology race. Just as we’ve led on semiconductors, biosciences, and advanced manufacturing, our investment in digital infrastructure shows that we are ready for the future—and helping to shape it.”

There is no inherent right or wrong in terms of development vision, and both the community amenity and volume-based economic development proponents have legitimate merit in their arguments.

With that said, data center development across the state totals 67 DATABEX projects since 2016, with combined estimated construction valuations of more than $75B across all stages of development.

Rushing to restrict that market without extensive research, detailed replacement models and, most importantly, extensive public and stakeholder engagement would appear, at best, ill-advised.