By Roland Murphy

Nearly 200 attendees braved some of the worst weather in recent Phoenix history to attend the “Yes In My Backyard: Ensuring Housing Supply for Arizona’s Future” Symposium at Papago Golf Club on Feb. 22.

The event was moderated by Nico Howard of HOME Arizona and Mark Stapp of the W.P Carey School of Business at Arizona State University, the two hosting organizations. While the three-and-a-half-hour symposium covered nearly every aspect of the current state of affairs in Arizona housing—from current economic and demand conditions to future policy planning—three core issues of concern to the construction and development community were top of mind for all the attendees and the various speakers:

- The severity of Arizona’s housing shortage,

- The slow pace of entitlements, permitting and other municipal processes, and

- The accelerating rise of NIMBYism and “resident” opposition.

The State of Housing

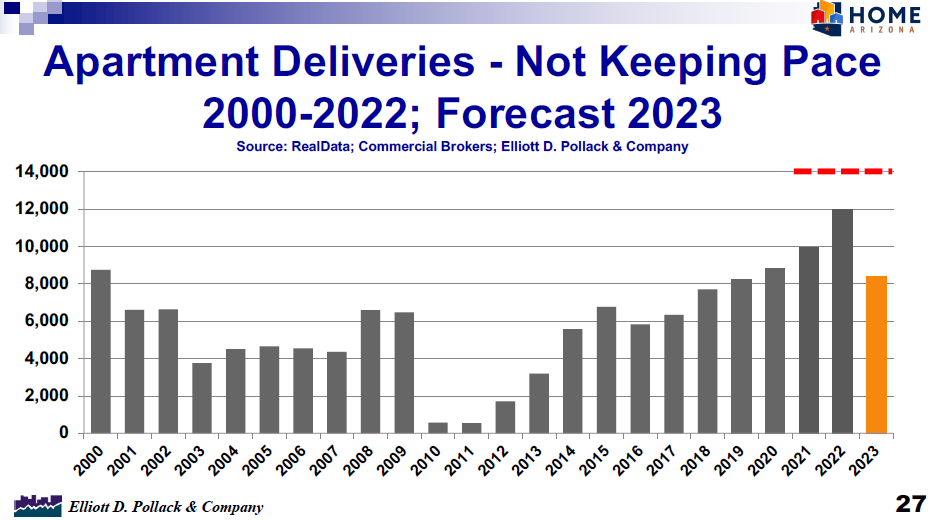

Early in the event, economist Elliot D. Pollack gave a detailed presentation on the scope and severity of the state’s housing shortage. He warned that the currently severe state of demand versus supply will require deliveries of at least 16,000 units/year for every year in the near future across all housing types, price levels and income levels. In 2021, the market delivered fewer than 10,000 units. 2022 saw roughly 12,000 units, and the 2023 projection is slightly more than 8,000 units.

The state’s impressive population growth and years of underbuilding led to dramatic increases in both purchase and rent prices and commensurate drops in affordability, which is harmful to economic development opportunity for the entire state. Pollack reported that in Q4 of 2015 Arizona had a National Association of Home Builders/Wells Fargo Housing Opportunity Index of 68.9, making it one of the most affordable markets in the country. By Q4 2019, that had fallen to 64.9, and it plummeted to 18.3 in Q4 2002, well below the national average of 38.1.

Pollack offered 10 ways affordability issues might be resolved, many of which—particularly on the policy side—would be echoed by other speakers and audience members throughout the day. Among them were:

- Increase supply across all types,

- Develop units in greater density,

- Improve municipal efficiency and organization when it comes to entitlements,

- Improve cities’ process speeds and lower their costs.

The last two points resonated well with most of the attendees, particularly when Pollack pointed out that regulation costs in metro Phoenix can be as high as $20K per door by the time a project delivers.

“Cities are reluctant to pay market rate for planners,” Pollack said. “As a result, they’re usually short of planners. In addition, most of the planners they hire are young and they’re trained in schools of architecture or schools of liberal arts. They’re not trained in schools of business; they have no idea how markets work. They have no idea of how what they do affects markets, nor do they care. That’s a serious problem.”

Later he said, “Under normal circumstances, the only constraint to getting back to where we were (in terms of supply and demand balance) is the governmental process. Circumstances are not normal because we are so short of supply. To get the housing market back to normal, we should be building even in this environment.”

Furthering that point, he said later, “During the current housing slowdown we have a unique opportunity to resolve many of the issues that could prevent a significant shortage from reoccurring when the economy turns. If you don’t act now, we’re going to be in the same situation we were in last year and the year before except on steroids. To meet the demand over a five-year period, you need to be building 42,000 units a year.”

City-level Problems and NIMBYism

City-level issues with entitlements and permitting and the increasing scope of project opposition were front and center in a panel moderated by Sunbelt Holdings CEO John Graham and comprised of former Phoenix Mayor Paul Johnson, Wood Partners Managing Partner Clay Richardson and Phoenix Deputy City Manager Alan Stephenson.

When faced with the question of how the overall process could be improved, Richardson pointed out one simple solution would be addressing the need for at-risk grading and drainage permits. Even when cities use private, on-call firms, there is simply too much work under the current approval and issuance model to allow for any real degree of responsiveness. Since the civil component is such a bottleneck, it adds months to the process, he said.

Johnson agreed but carried the point farther. He said planning departments need to have oversight authority over other departments, such as streets, transportation and fire, rather than serving as a mere coordinating body.

He added that cities often see themselves as separate from the development process and that, while labor volume and experience is an important issue, process efficiency is a greater drain on timeline progress than mere worker counts. Johnson estimated that half of the time in bringing a project to fruition is spent dealing with cities.

Discussing the issue of opposition and NIMBYism, Richardson stressed that a great number of good projects are not viable in the current environment because of opposition and the protracted entitlement process. He speculated that fear keeps many potential projects from advancing in the first place.

He added, however, that a change is starting to happen. He sees an entire demographic of people who are impacted by the slow pace of development and the low supply of housing are beginning to mobilize. He said they have come to realize they simply cannot continue to live unless things change. Richardson stressed that conversation, discussion and outreach are vital and that developers, advocates and other stakeholders need to work together as a coalition to amplify those people’s voices and, more importantly, get them to vote in local elections for candidates that represent their needs.

The economic and process points of discussion were center stage later in the morning when former Gilbert Mayor and current Horizon Strategies CEO Jenn Daniels and former Arizona State Senator and current ASU Professor of Practice Sean Bowie presented.

The pair emphasized a need for policy reform at the state level and down into individual cities. Among their primary points were:

- Expediting the zoning and entitlement processes,

- Streamlining design review,

- Empowering the state Department of Housing to grade local processes,

- Setting reasonable schedules for application reviews and penalties for failure to perform,

- Establishing universal zoning definitions at the state level, and

- Requiring a set 30-day public comment period.

The last two points resonated particularly well. According to the presentation, the key goal for definitions is, “Identifying logical and predictable zoning definitions at the state level allows for comparison of zoning between municipalities, transparency in the process, and clarity for developers.” Many in the audience supported the idea, saying that uniformity across jurisdictions would be a savings in terms of certainty, efficiency, planning and stress reduction from one city to another.

Audience Input

In advocating for a set 30-day comment period, Daniels and Bowie tapped into the deep vein of NIMBY frustration that had woven throughout the entire symposium. The text of the point said, “By providing a set, 30-day citizen review period embedded into the process, citizens and stakeholders would have an opportunity to submit questions and share opinions about the merits of a case.”

Members were quick to pick up on and comment on the fact that a set would also reduce opponents’ ability to overpower debate and shut down review and approval at multiple points along the process, as they can now.

Frustration with opposition groups and their efforts to derail projects was a recurring theme throughout the day. Among the items brought forward during question and comment periods were the fact that opposition groups are unifying. No longer are speakers at planning and council meetings just the residents who live in a proposed project’s defined impact area. Opponents from Surprise to Chandler are uniting online to lend support to each other’s efforts in a coordinated fashion.

One attendee said, “The rules don’t apply. They want nothing less than the ability to define where development can happen.”

Mesa Councilmember Julie Spilsbury commented from the audience that it can be hard to counter constituents for the sake of growth and municipal improvement, but that it is an obligation that needs to be fulfilled.

She also said it was astounding, to her, that projects continue to run into ongoing stigmas that have been steadfastly and uniformly disproven, such as allegations that apartment development increases crime or that renters are less desirable residents than homeowners. She said she has had to repeatedly address perceptions of existing residents that new residents do not constitute, “Those people,” as in, “We don’t want those people living near us.”

She also expressed frustration that opponents can still manage to view residents who can afford $2,500 or more in rent as transitory, undesirable neighbors.

Many attendees agreed with Richardson’s panel statement that the development community needs to work to empower the silent minority to raise their voices and speak out in favor of increased supply and affordability. It was pointed out repeatedly, however, that it is easier to mobilize people against something rather than in support of it. They expressed hope, however, that Johnson was right and that a change is beginning to foment.

In introducing the event, HOME Arizona’s Howard touched on a key point of both hope and frustration that came back many times. He said the group has made extensive outreach to public officials and the development community but had yet to have a great deal of success in moving the community to present a united front in which companies actively supported each other’s projects whether they had a direct stake or not.

Speculation was rampant throughout the event as to what could be achieved if both united developers and beneficiaries of increased supply and affordability were to expand as social forces in the process, a sort of opposition to the opposition. While the speculation was abundant and the actual progress has been slow, attendees had reason to leave the day with a sense, however modest, that some amount of hope might be justified.