By Roland Murphy for AZBEX

Much has been written in the last several months on Arizona’s reduced allocations of Colorado River water, the ongoing Millennium Drought and the future of growth and prosperity in the state.

Unfortunately, much of what has been written has been incomplete, hyperbolic or badly reported. Rather than nitpicking the ins and outs, we decided to take a broader and more expansive overview in hopes of setting the record a little more straight and providing our readers a more encompassing looking into the state of water supply and development in Arizona

The State of Water

We won’t waste space by rehashing in detail the Colorado River allocation cuts. If you’re reading this column, you’re probably already aware that the state’s 2023 allotment will decrease by 592,000 acre-feet, representing 21% of the normal delivery and an 80,000 acre-feet decrease over 2022.

While the Colorado is a major Arizona water source, it’s not the biggest. The state has four primary water supply sources. According to the Arizona Department of Water Resources, the main source is groundwater (41%), followed by the Colorado (36%), in-state rivers (18%) and reclaimed water (5%).

In his recently released Southwest Water Monitor Special Report for Q3 2022, Colliers Research Director Thomas Brophy explains the situation concisely by reporting: “The Colorado River Basin continues to experience drought and the impacts of hotter and drier conditions. Based on the January 1st projected level of Lake Mead at 1,065.85 feet above sea level, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior has declared the first-ever Tier 1 shortage for Colorado River operations in 2022. This Tier 1 shortage will result in a substantial cut to Arizona’s share of the Colorado River – about 30% of Central Arizona Project’s normal supply; nearly 18% of Arizona’s total Colorado River supply; and less than 8% of Arizona’s total water use. Nearly all the reductions within Arizona will be borne by Central Arizona Project (CAP) water users. In 2022, reductions will be determined by Arizona’s priority system – the result will be less available Colorado River water for central Arizona agricultural users.”

As of 2019, the state’s three main water use sectors, again according to ADWR, are Agricultural (72%), Municipal (22%) and Industrial (6%). Agricultural uses will take the hardest hit under the Colorado allocation reduction, and much has been made of the difficulties to be expected in Pinal and Yuma counties – two of Arizona’s agriculturally intensive production areas.

Brophy notes the shift across usage types as Arizona becomes more urban. “As urban development expands into agricultural lands, water demand is shifting from agricultural to municipal and industrial uses. Depending on the boundaries used to measure water use, the proportion of water demand shifts from predominantly municipal to agricultural.

“Until 1990, more water was used in the Phoenix AMA for agriculture than for cities. By 2019, half of all water was used by municipalities and only 30% was used for agriculture.

“In Maricopa County as a whole, irrigation accounted for 62% of the county’s water use in 2015 (the last year data was collected), while municipal use accounted for 37%.”

Arizona’s Conservation Success

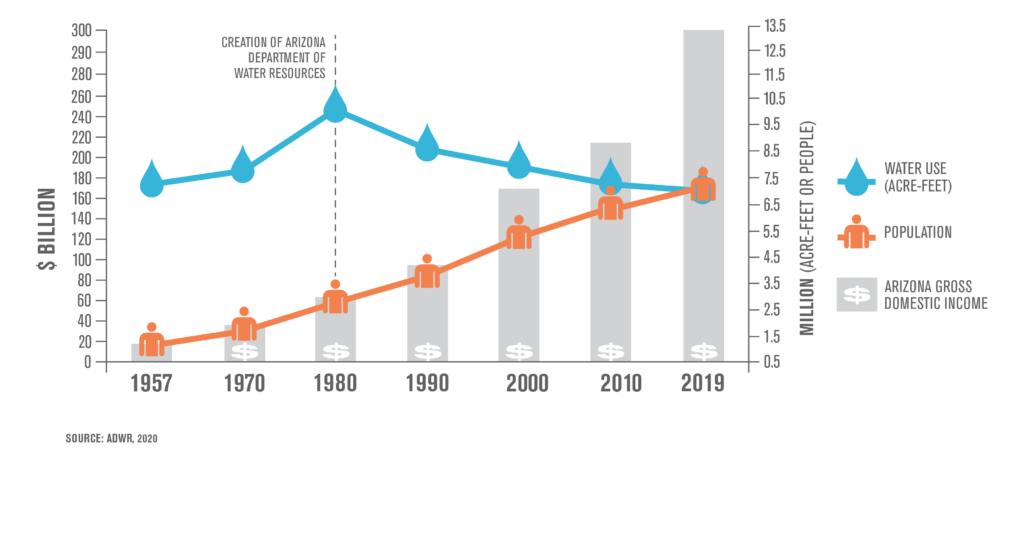

What has most often been overlooked or omitted in general news articles on Arizona water is the state’s astounding efficiency in water conservation and management. According to U.S. Census Bureau data, Arizona’s population in 1970 was approximately 1.78 million. By 2020 the count had boomed to 7.17 million. The state’s water use has remained virtually the same, ADWR says, through investments in conservation, infrastructure and reuse.

Another point that is frequently overlooked is Arizona’s success in long-term water planning. As a result of collaboration and plan management among water providers and private parties, more than 3 trillion gallons of water has been banked in underground storage for future use. ADWR says that’s enough volume (at 2020 usage levels) to serve Phoenix’s needs for 30 years.

None of this is intended to imply there is not a crisis or that we can kick the planning can any farther down the road, but it does mean there is a little more breathing room than some reports would lead one to believe. It also undercuts the claims of some outliers in the conservation community that the state’s efforts have been lax.

Water and Development

In general, if you’re going to build something, you’re going to have to ensure there’s water for it. It really is that simple, but, of course, simple and easy are rarely the same thing.

Fortunately, since water management and supply are key considerations, the construction and development industries have gotten adept at addressing them.

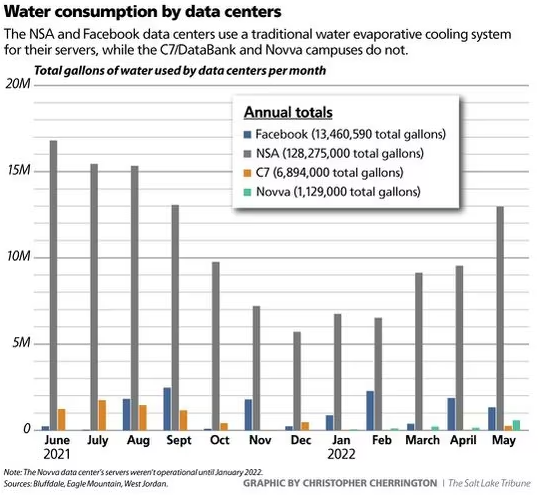

Take data centers as just one example. In the August BEX Companies Leading Market Series program on advanced manufacturing, JLL Capital Markets Group Sr. Director Carl Beardsley – whose team focuses on data center opportunities – explained how data centers have gone from highly wasteful to highly efficient water users.

“The older school data centers – especially in arid climates… – you would use certain cooling methods that would use a lot of water – evaporative cooling. It’s more efficient. It’s cheaper… That’s flowing through to the end user as bad perception of, obviously, using so many resources that are constrained,” Beardsley said. “So, everyone’s shifted to a new cooling technology of closed water loops, where you really just fill the water once and you use the same water over and over to cool.”

According to Beardsley, the old technology can regularly use 120 million gallons of water/month, versus as little as one million for a closed loop system. (AZBEX, Aug. 2)

Unfortunately, even as the realities of efficiency have become more commonplace, the myth of inefficiencies has added fuel to the rhetorical fires of anti-development forces in neighborhoods and in municipal government. The Avondale Planning Commission in November 2021 recommended against a data center project, citing fear of water supply impacts as a key reason for their denial, even though the center was of the more efficient closed loop design. (AZBEX, Aug 9)

That empowerment of opposition was a point raised early in a recent conversation with Jason Morris of Withey Morris PLC – one of the state’s leading zoning and land use law firms. Morris said, “What I’ve experienced of late is that jurisdictions that already have an anti-multifamily bent or a slow-to-no growth bent love to use this as a reason to not approve or factor in not approving new development. The irony is that new stuff is so much more efficient, oftentimes, than these… large acreage, low-density existing housing stock. They insist, somehow, ‘Oh, we’ve got to be careful. We can’t start approving apartment buildings or doing more because, by golly, we’re in a water crisis.’ It’s being used in a very convenient and detrimental manner in some instances.”

He went on to say that a major problem in efficient water usage is the combination of antiquated infrastructure and large acreage/low density developments. “Oftentimes, there’s leakage and inefficiencies in the older infrastructure that, when replaced with new infrastructure becomes a net gain, rather than a loss of water, even with higher densities,” Morris said.

“Don’t take anything that I’m saying to belittle the overall picture. I’m in no way, shape or form a drought denier. I recognize it. I’ve lived here the better part of my life, and I understand what I’m seeing. It’s a legitimate problem. I just think that due to good planning and resources available in the state that we have some options that other areas in the desert don’t. We can always be more efficient, and there are a lot of areas where we can trim water use that we wouldn’t feel it as much. I think there’s a lot of belt tightening when it comes to water, but we’re also blessed with surface water, ground water and a CAP allocation.”

Regarding the hyperbole in much of the reporting on the Colorado River and CAP reductions, Morris called much of it simple fear mongering.

“What disturbs me about that approach,” he said, “is that it is not taking into account the consequences of the actions that are being taken. It’s irresponsible because people tend to forget at the end of the day we’re competing against other cities. It’s wonderful that we’re all part of this great nation, but we’re in head-to-head competition with Denver and Austin and we compete with Las Vegas and other cities… At the end of the day, I use every one of these articles to frighten users away (if I’m an economic development official in a competing city). ‘Do you really want to relocate to the Phoenix metropolitan area? Those folks are just about out of water. How good is that going to be for your workforce? What does that mean for your continuity of manufacturing? Are you sure you want to do this?’ We know that there’s much more to that story.”

Asked to consider the next five years of water-related issues in Arizona, Morris said the state is going to see restrictions on both supply and demand. “If we’re smart, and if we’re reasoned, and if we have good leadership, then the approach will be recognized that we’re still going to have net influx of population, so we don’t have the option of shutting the industry down. We’re still going to have to provide new housing. But I think that new housing is going to be much more environmentally sensitive and cognizant of our desert environment both in the design of the units themselves but also in their water consumption. I do not believe that we will take for granted a never-ending supply of water.”

He went on to say, “Just as important, we’re going to – in the next five years – see alternative sources, whether it’s desalination or the ability to pipe water from other regions. The cost of water, much like the cost of oil, dictates the lengths we’re going to go to make that resource available.”

Addressing Current Needs and Future Supplies

Let’s accept for the sake of argument that – barring divine intervention or similar unlikelihood – the drought is not going to end, reverse itself and replenish Arizona water supplies within the next few years.

Let’s also accept that more Colorado River allocation restrictions are going to come, and they’re likely going to continue to be stilted more toward California’s benefit and have disproportionate impacts on Arizona.

So, what do we do? While there is no one all-encompassing solution, there are a several options that could, in various combinations, ease the crisis and potentially improve the situation for decades to come, if not permanently.

Unfortunately, they all require heavy economic investment, resource allocation, cross-interest collaboration and an abundance of political will and focus, so the odds cannot be set at better than even money.

First, we need to address the near-term supply. Even if the Colorado River allocations were revised tomorrow, it wouldn’t change the amount of water available to draw from, and Lake Mead levels will still trend downward.

In the Colliers Southwest Water Monitor report mentioned earlier, Brophy included a possible one-time solution that, while wildly ambitious, is also exceptionally straightforward. We include it here unedited:

Lake Mead, according to the Bureau of Reclamation, needs 2-4M af (acre feet) which equals 1.3T gallons of water to stabilize the lake. Currently, Lake Michigan has continued to swell with recent studies estimating the lake needs to drop, a minimum, of 6 inches, to a high of 27 depending upon study.

In this scenario, a 1-inch drop in Lake Michigan equals 400B gallons. We need 1.3T gallons = 3.26-inch drop

Aside from the international and multiple state agreements which would need to be signed, and that would be a feat in-and-of itself, is how would we transport the water?

Well, I figure 30+ converted Boeing 747s which can carry 17.5K gallons of water and a fleet of railcars could handle it over the course of 2 week period to the tune of $5-10B depending upon transportation type, fees, payments, transfers and otherwise.

Please note that this is a one-time solution only and a much better one would be desalination via membrane which extracts both water and salt, other minerals and does not re-inject back into the ocean.

The high-end price tag of $10B is a comparatively trifling sum compared to the ongoing economic ripple effects of Lake Mead becoming a “dead pool” and the loss of electricity from the Hoover Dam. Best of all, the infrastructure already exists, and it would address not one water volume problem, but two. With enough focused saber rattling, the operation could be up and running in a matter of months.

Assuming Brophy’s idea were implemented and successfully carried out, we still need an extra-natural means of stabilizing the supply. There are two proposals that keep coming up, and both present major challenges.

The Mississippi Pipeline

The first recommendation is the construction of a roughly 1,500-mile pipeline to divert Mississippi River floodwaters to the Southwest. While the ultimate destination varies among suggestions, Lake Powell is a commonly stated endpoint.

One particularly aggressive variation on the recommendation would divert 5.5 trillion gallons to Lake Powell in 254 days.

While the plan is simple on its face, the reality is ridiculously complicated. First, Mississippi River flood water levels, and water levels in general, are unpredictable. Just this week, barges were grounded and traffic was halted in the lower Mississippi basin because of low water levels. A threshold would have to be established as to when the pipeline could be engaged. It would have to be built to handle high-volume capacity years, and then some years it wouldn’t be able to be used at all.

Second, despite the damage caused by flooding, it is a known circumstance, and the infrastructure is largely in place to accommodate it. The entire ecosystem is, in fact, dependent on silt and other deposits from annual flooding to offset storm damage on the Louisiana coast and barrier islands. It would be impossible to expect any degree of significant support from officials in Mississippi River states or from environmental groups or national resource management agencies.

Third, the logistics would be a decades-long quagmire. Even without taking into account the physical construction – which would be the easiest to address of all the problems associated with the pipeline idea – take 15 seconds to consider the difficulties in acquiring the land, rights of way, permits, impact studies and other administrative minutia the project would entail. The most conservative estimates to address the legal requirements predict a 30-year timeline. The smart money moves that even farther out.

Desalination

In January, Governor Doug Ducey proposed a desalination plant on the Sea of Cortez that would pipe treated water to Mexican farmers and other users south of Yuma. Once in place, Arizona would purchase part of Mexico’s share of Colorado River water for its own use.

There are at least as many problems with desalination as there are with a pipeline, however. First, desalination is a highly energy-intensive process. If traditional power sources were to be used, the process would almost certainly die at the hands of the environmental lobby worried about fossil fuels and greenhouse gas emissions.

The most logical power source for a large-scale desalination plant is nuclear. While there are legitimate concerns about nuclear power, there is an even greater irrational degree of concern stemming from more than 40 years of entrenched opposition. The “No Nukes!” movement was a foundational component for modern environmentalism.

In recent years, however, the environmental community has begun to reexamine nuclear energy, since it is greenhouse gas-free and the specter of nuclear waste has been shown to be unnecessary as a result of modern designs effectively recycling materials that would have once been discarded. Still, the cultural memory, both among environmentalists and the general public, remains deeply entrenched.

The other great difficulty would be, again, the political will and complicated agreement structure that would be needed to implement such a plan. Two federal governments, multiple states in two countries, a myriad of regional and municipal governments, administrative agencies, individual landowners and others would have to come together in some form of consensus, and then all the administrative infrastructure of design, environmental study, permitting, construction, etc. would have to be executed, as would exceptionally complicated funding structures and allocations.

There is no one answer, and none of the disparate answers are easy to implement. There is, however, hope. In June of this year the Arizona State Legislature approved Governor Ducey’s $1B water augmentation fund to explore and start implementing solutions to Arizona’s long-term water needs.

It will not be enough, but it is a start, and the first step to generating political capital is generating actual capital. Perhaps that capital, combined with all the exploration and discussion that has gone before, will find the way to Arizona’s water future just around the next bend.