By Roland Murphy for AZBEX

As a twice-weekly publication, we don’t usually cover breaking or “spot” news simply because it’s dated by the time the magazine arrives in readers’ inboxes. That said, the drama over the past few weeks concerning the risk of a rail strike in the U.S. – and the potential havoc even a brief stoppage could have on the brittlely fragile supply chain – warrants an exception.

As of 6:45 a.m. Eastern on Thursday, Sept. 15, the Associated Press was reporting President Joe Biden’s announcement that a tentative deal had been reached following protracted last-minute negotiations between Administration representatives, rail company officials and the 12 labor unions involved.

A strike had been expected to start as early as Friday morning. The prospects for an agreement took a hit on Wednesday after one union representing 4,900 workers – the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers District 19 – voted to reject a compromise measure reached late last month. Despite rejecting the deal, IAM leaders had agreed to delay a strike until Sept. 29 to give the last-minute negotiations a chance.

After ratification between the negotiators, the agreement announced Thursday morning will go to members of the 12 affected unions for a vote after a “cooling off period of several weeks,” according to AP.

Whether or not that agreement will be approved, the Administration has bought itself – and, more importantly, the economy – a few weeks of ongoing rail operations heading into both the end of the quarter and the midterm elections.

The Dispute and the Tentative Agreement

In the five years before the pandemic, the U.S. rail industry cut nearly 25% of rail worker jobs and instituted strict work scheduling and attendance protocols, which workers and their union representatives say have led to untenable working conditions.

A Sept. 14 New York Times article reported, “Regulators and the unions representing rail workers portray the vulnerabilities of the rail network as the outgrowth of the decision by major railroads to reward their shareholders at the expense of their customers.

“The cuts came as part of what the industry calls Precision Scheduled Railroading, in which the carriers limit service to reduce their costs.”

The August tentative agreement, which was derived from recommendations made by an emergency panel created by the Administration, “called for 24% raises and $5K in bonuses in a five-year deal that’s retroactive to 2020. Those recommendations also include one additional paid leave day a year and higher health insurance costs,” according to AP.

The revised agreement announced Thursday keeps the pay increase and bonus but added changes to the railroad companies’ attendance policies. Workers will now be able to take unpaid days off for medical appointments without incurring penalties. Union representatives said the deal sets a precedent for future negotiations.

The Supply Chain Snapshot

This column will not be a white paper on global economics. The pandemic and the resulting rebound in demand has made all of us far more aware than ever before of the glass-fragile state of the global supply chain for everything from energy inputs to steel and mill products to roofing screws to, yes, toilet paper.

June’s BEX Leading Market Series discussion focused on supply chain issues and rising construction costs, and we won’t rehash here the entire scope of the problem the Architecture/Engineering/Construction world has come to factor into its daily operations at the industry, company and project levels. (AZBEX; June 10)

We will point out – since there are so many daily trees still to wend through that it can be difficult to remember the forest even exists – that even though construction costs are still being ravaged by inflation, rising interest rates and a host of other factors, global supply chain pressures have been easing for the most part.

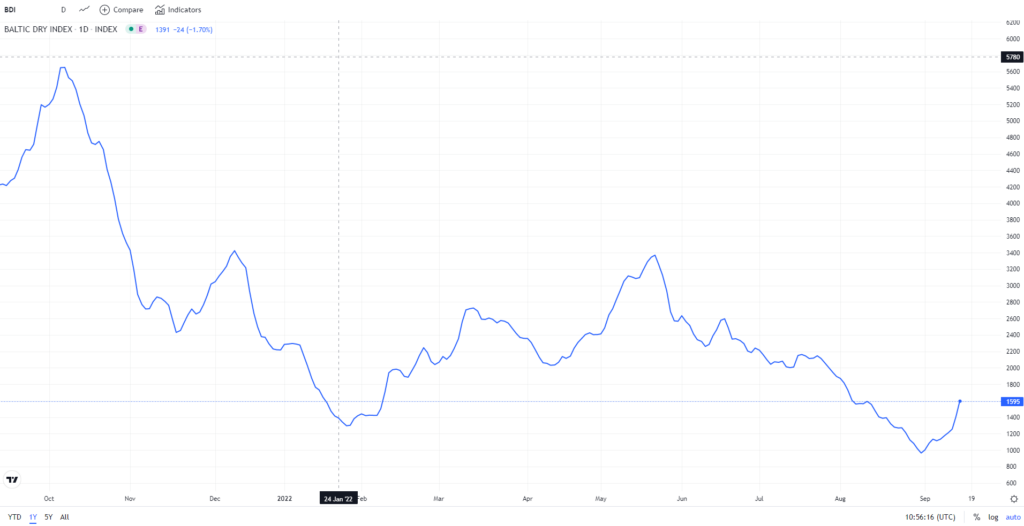

The Baltic Dry Index is a benchmark that measures the cost of shipping goods worldwide, as reported daily by the Baltic Exchange in London. The Index is a composite of three sub-indices that focus on different sizes of bulk carriers for ore products, coal, grain and other materials. It is considered a leading supply chain indicator.

The BDI hit a high for 2022-to-date on May 23 with a score of 3992. The high for the preceding 12 months came in Oct. 2021 at 5657. By the end of August, the Index had fallen to 982 before beginning a steady climb again to close at 1600 on Sept. 14.

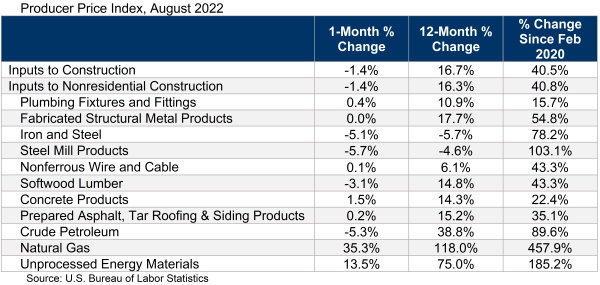

The slow easing of supply chain pressures has begun to ripple downward into construction input costs. Associated Builders and Contractors’ analysis of the Producer Price Index for August showed a decrease of construction input prices of 1.4%. This follows a 1.8% decrease in July. While those decreases can largely be attributed to a modest leveling out of inflation in the study period, material availability and deliveries also played a key role.

In summarizing the July report, ABC Chief Economist Anirban Basu said, “A weakening global economy and ongoing supply chain adjustments have resulted in significant declines in the prices of a number of key commodities, ranging from oil to steel.”

Still, input prices are 16.7% higher in Aug. 2022 than Aug. 2021, and 40.5% higher than in Feb. 2020.

A U.S. rail strike would have shattered all these modest improvements, and even a brief stoppage would have generated geometrically expanding ripple effects. Another lesson we learned from the pandemic is that best guesses on crisis resolutions are not worth the virtual ink it takes to publish them.

The U.S. Department of Transportation’s Freight Railroad Administration reports that, as of 2020, 28% of U.S. freight is moved by rail.

Multiple experts and trade groups, including the Association of American Railroads, estimated the direct impact of a rail strike on the U.S. economy at $2B/day. The protracted and indirect impacts would be anybody’s guess, since there is not capacity in the trucking or air freight sectors to absorb the impact. A March 2022 report in Forbes estimated the truck driver labor shortage at 80,000 workers.

Rail has already long been described as among the weakest in a supply chain largely comprised of weak links. The industry has been criticized for focusing more on raising its collective stock valuations through share buybacks and cost reductions rather than investing in improvements to increase capacity and alleviate congestion in the face of a protracted demand surge.

The Sept. 14 Times article quoted trucking industry executive Oren Zaslansky as estimating a rail stoppage would be the equivalent of taking 500,000 semis off the road. “This would be pretty painful in any context, and we finally just got this thing calmed down,” he said.

The early predictions are that the union members will agree to accept the new deal and that freight shipping by rail will mostly continue uninterrupted.

Still, in an industry still reeling from the pandemic’s impacts and still having to pivot on a monthly/weekly/daily basis to cope with the “new normal,” flinch responses in A/E/C leaders that had, perhaps, only just begun to settle down have been jolted back to high alert wondering where the next shock to the system may arise.