By Roland Murphy for AZBEX

Last month, the American Planning Association Arizona Chapter and the Arizona Association for Economic Development conducted a workshop on affordable housing in the state.

The presenters were:

- Ashlee Tziganuk with the Morrison Institute for Public Policy at Arizona State University,

- Jerry Stabley, former community development director for Pinal County, and

- Bob Workman of R.L. Workman Homes in Sierra Vista.

In individual presentations, the group explained the policies and problems currently impacting affordable housing in the state from both legal and development perspectives and offered insights as to what can be done to better address the problems moving forward.

Legal Barriers to Affordable Housing

The first presentation was delivered by Research Analyst Ashlee Tziganuk from ASU’s Morrison Institute for Public Policy.

She began with an overview of the current housing situation, including the oft-cited current shortage of 270,000 housing units, and explained the lack of supply is a primary driver for the state’s ongoing housing cost inflation. According to the latest research, 44% of Phoenix area households qualify as “cost-burdened” – paying more than 30% of household income for rent. Around the state, those percentages range from 40% to 60%.

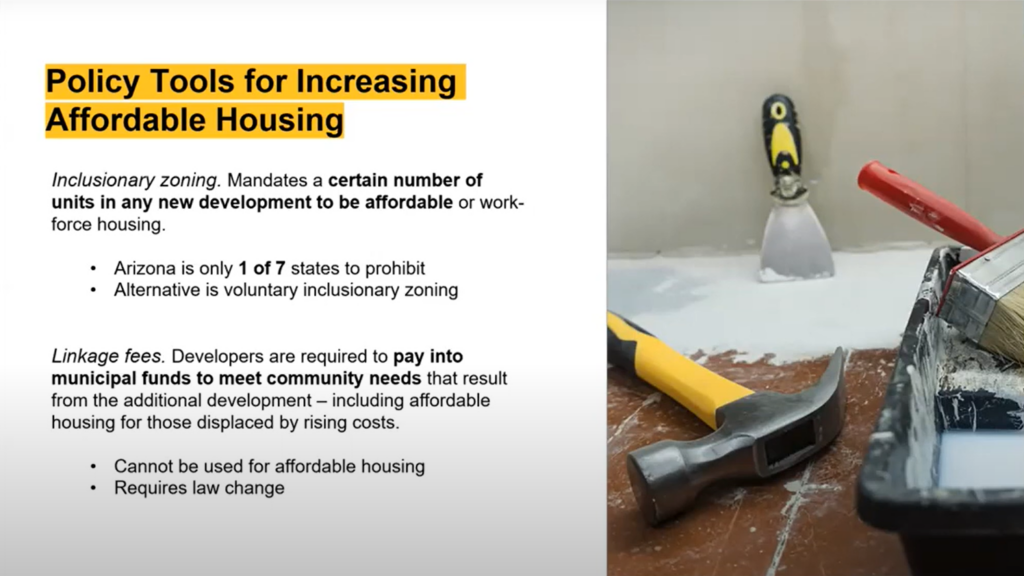

Tziganuk next turned to policy factors impacting affordability, including:

- Inclusionary zoning, in which a percentage of all newly developed units are designated affordable or developers make a payment in lieu to fund affordable development;

- Rent control and stabilization, where rent increases are capped either to a set rate or for the term of a renter’s occupancy;

- Short-term rental regulation, including limits on the number of STRs and/or the establishment of taxes or fees paid by STR operators that fund affordable development, and

- Tax Increment Financing and Industrial Development Authority programs, using a designated portion of property or sales taxes to fund affordable development or using IDA-backed bonds for affordable financing.

All of these means and methods to incentivize, finance or promote affordable housing development have some degree of restriction – including outright bans in some cases – at the state level. Tziganuk also mentioned factors such as:

- Various state legislative constraints, such as the Private Property Protection Act and the state constitution’s Gift Clause that constrain municipalities’ options for creative incentivization and development programs, and

- Municipal barriers, such as restrictive zoning, density caps, parking space minimums, accessory dwelling unit restrictions, a preponderance of single-family zoned property and the empowerment of so-called “neighborhood opposition” and “NIMBYism,” that further complicate or restrict affordable development.

Tziganuk then summarized a number of various efforts that have been employed elsewhere. Many of these methods are fairly recent in their implementations, and valid, time-based effectiveness data are lacking. In addition to revising or eliminating the restrictions listed above, she discussed efforts that have included:

- Eliminating single-family zoning, as has recently been implemented in Minneapolis;

- Establishing “By-Right Development,” in which development approvals become rule-based rather than discretionary;

- Establishing Affordable Housing Overlays, where affordable housing becomes an approved development type in addition to an area’s existing zoning, and

- Creating Affordable Housing Districts, in which the zoning encourages the creation of diverse housing types and establishes greater flexibility in development standards.

Planning Methods to Increase Housing Stock

Following Tziganuk was retired Pinal County Community Development Director Jerry Stabley, who began with some interesting tidbits on the state of the market and the history of single-family zoning.

While housing affordability was, until recently, one of Arizona’s primary draws to attract new business and economic development opportunities, Stabley said the overheated market conditions have caused Arizona and Phoenix to plummet in the standings, to the point that Phoenix now ranks as the 15th least affordable market in the country for housing.

He also said he had talked with experts at the Maricopa Association of Governments about the 270,000 needed units estimate from the Arizona Department of Housing – as well as estimates from other organizations – and learned that no group’s estimation models have been able to be replicable because of the number of variables and assumptions.

He then explained the current state of the market in historical terms. Using 2021 inflation-adjusted dollars, an average home cost $172K in 1965 and costs $375K now, a 118% increase. Meanwhile, the average household income has only increased from $59.9K to $69.2K, just 15%.

The average U.S. home now costs 5.4 times the average person’s annual income. The recommended target ratio for affordability is 2.6. In Phoenix, the ratio is 4.6.

Turning the discussion to zoning, Stabley said 70% of U.S. residential zoning is single-family. He chalked the preponderance up the facts that it allows for predictable development, offers quiet neighborhoods, protects property values as an investment and allows for a reasonable use of public services.

On the challenges of single-family zoning, he pointed out that the larger mortgages and lot sizes are prohibitive for many people and that single-family is largely automotive-dependent – which also adds to living expenses.

Stabley then covered the various types of multifamily and first turned his focus to the so-called “missing middle” – one- and two-story structures of up to eight units – that usually physically resemble the single-family homes in a neighborhood, fit in low-rise areas and provide a lower-cost housing alternative. On the downside, homeowners and builders often assume small-volume multiplexes will lower the value of adjacent properties. The developments also add a comparatively small number of units to the overall mix. Lastly, most zoning codes do not allow such divided uses in single-family-designated areas.

Summing up the “missing middle” component’s value, Stabley said that while expanding that option was worthwhile, he did not see it as a panacea for volume additions. “Could it be a good thing for people to be able to live in these neighborhoods…? Absolutely. Will it really address our issue if we truly have 270,000 units that we’re down? I kind of doubt that it will.”

Moving to multi-story apartments and condos, he listed the advantages of lower costs compared to single-family, the larger number of units per property, common amenities and the opportunity to better utilize multiple transit options. The disadvantages include the large investments associated with development; the more transitory nature of residency; the NIMBY concerns about neighborhood character, obstructed views and reduced property values, and the fact that such developments normally require rezoning.

That rezoning process can, of course, be cumbersome, expensive and time-consuming, particularly in the face of neighborhood opposition and the sensitivity of elected officials when it comes to addressing that opposition. Cost additions include the potential for the project to be rejected, the expense of hiring experts and commissioning studies to address concerns, and the extension of timelines.

He used the Greenbelt 88/Lucky Plaza redevelopment proposal in Scottsdale as an example of the rezoning burden projects face. AZBEX readers will no doubt be familiar with the story, as we have covered it extensively in a series of articles and columns as a case study on the rise of organized opposition, agenda-setting by oversight bodies, the expansion of NIMBYism and a host of other approval and development issues.

To briefly summarize, the Greenbelt 88/Lucky Plaza redevelopment proposal was a request to rezone a dying strip mall in Scottsdale to multifamily/commercial mixed use. Even though there was no single-family or other residential use adjacent to the property, neighborhood and City Council opposition led to two years of delays and plan revisions – including one last revision from the Council dais during the final approval hearing – before the project was allowed to proceed.

“If I were in the State Legislature, if I looked at something like that, I would say, ‘Oh man, that’s just not acceptable,’” Stabley said. “That’s really way too long to have those kinds of negotiations take place.”

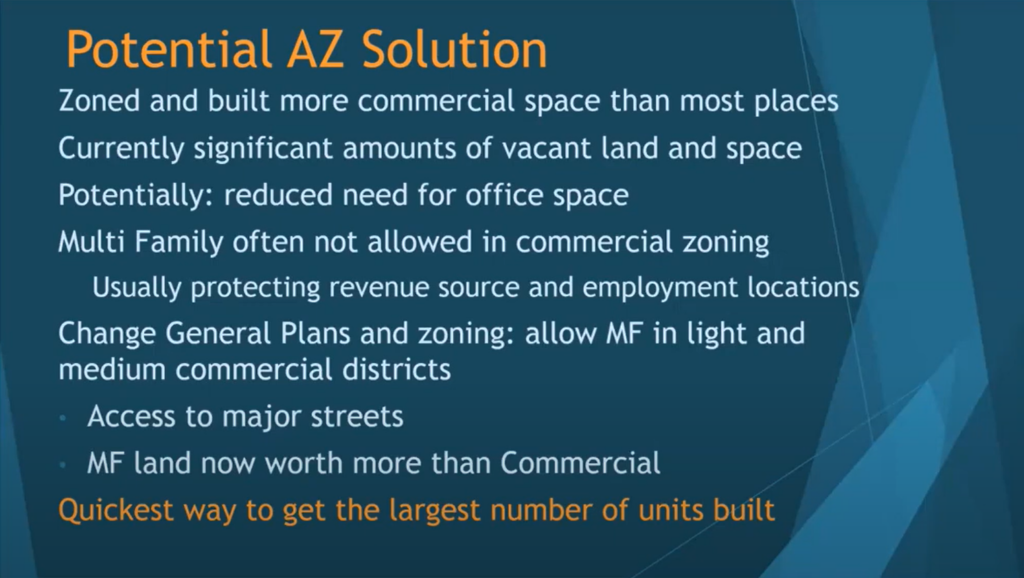

One solution Stabley recommends is addressing the over-focus on commercial zoning that was instituted during previous development cycles. Such development was highly popular because sales taxes and commercial uses were significant sources of municipal and infrastructure revenue. With the advent of hybrid and remote work and online versus brick and mortar retail, Stabley recommends revising commercial zoning requirements – which often specifically exclude multifamily – to promote better land use, increase unit counts and reduce vacancy.

“This would be the quickest way to get the largest number of units built,” he said. “If somebody could come in, build in these commercial districts, use these relatively large parcels that have services and access to transportation – including transit – and could minimize the impacts on single-family residential… this could be a way that we could address this issue and get more units in the short run.”

Stabley said the State Legislature’s Housing Supply Study Committee is examining the issue and the Dorn Policy Group and APA AZ are working with interested parties on a proposal that could reduce the local political issues. The Committee’s work is expected to wrap up next month, and Stabley expects there is a “good chance” the Legislature will act on housing supply.

“That’s one of the reasons why we’re working with them – to see if we can help to tailor that program and maybe get something that’s more acceptable to the municipalities and perhaps find a way to reduce the local political issues…. Is there a way to take this out of the political arena to some extent so that somebody doesn’t have to work with the neighborhood for two years to get zoning approval?”

The Private Developer’s Perspective

The workshop’s final session was a far-ranging, hour-plus discussion and question-and-answer period between attendees and Bob Workman of R.L. Workman Homes in Sierra Vista.

Early on, Workman cautioned against the implementation of “gratuitous” standards imposed on developments. He said there is a risk in adding requirements to a project based on planners’ “group dynamic” rather than actual market needs.

He cited open space requirements as one example, saying planners and buyers often say they want it, but ask if buyers are willing to pay for it, particularly given water demand and associated costs.

Other holdups impacting the pace and scale of development Workman mentioned included environmental concerns, land supply for private development versus the massive inventory of publicly owned land, infrastructure and improvement costs, and the multiple laying on of requirements from municipal engineering departments.

“Growth has to pay for itself,” Workman said. He cited the rising costs of building permits, utility placement, and other development.

“Literally, the entire site is funded. It’s handed to the municipality or governing body. Then you have to warrant it for two years. Then we somehow get beat up that growth didn’t pay for itself,” he said. “I don’t get it. There’s a taxable revenue unit in perpetuity that’s built there. I guess the United States of America didn’t reach this level of infrastructure before we had impact fees,” he joked.

“It’s just a way of funding something else. I know it’s a little challenging to a governmental body, but, in essence, I’m the tax collector for it,” he said. “The end user pays for it…, but when we’re talking about affordable housing, you can’t up requirements and then expect costs to go down. That dog won’t hunt. Somebody’s going to pay for that.”