By Rebekah Morris for Arizona Builder’s Exchange

Inefficient contracts… Lack of oversight and documentation… Resistance to market trends… These are a few of the issues plaguing one of the poorest public school districts in a state that Governing.com has ranked 49th in per pupil funding as recently as June 2018.

Forty-five million dollars in bond funds are just beginning to be expended in Alhambra Elementary School District. The $45M bond passed by voters in 2017 is dedicated to new gymnasium buildings, a new performing arts center, renovations to libraries, classroom spaces, and general building needs. Before 2017, the district had not issued a bond in 25 years.

The annual impact to the average homeowner is a modest $40.35, based on a median home valuation of $49,630. Both the aggregate bond amount and average home value are near the bottom for school districts in Maricopa County.

Knowing this, one would expect the district staff and the design and construction community to squeeze every last penny from bond projects.

That, unfortunately, does not appear to be the case.

While inspecting numerous public records — including the contract for the architect and the four current construction contracts — we found opportunities for efficiencies unrealized, disregard for industry standards, and a lack of documentation and due diligence the open-book contracting methods deserve.

Project and Process Overview

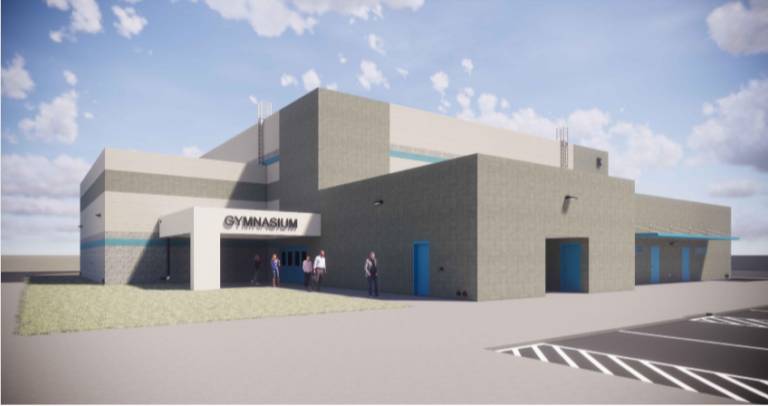

The district is using a prototype design for new gymnasium buildings on a total of eleven campuses. In an interview with AZBEX on October 25, Jeff Stratman, district legal counsel and construction project manager for Alhambra Elementary, said the intent was to develop a typical building that could be slightly modified across different campuses. Stratman’s responsibility includes selecting contract types for the construction services procurements.

The district is using a variety of contract delivery methods. The design services contract was procured through an existing cooperative contract, 1GPA. Four Architecture firms were interviewed, and an objective scoring metric was used to select ADM Group, Inc. as the Architecture firm of Record for all bond projects.

Moving to the construction procurements, two contracts for new gyms used a traditional design-bid-build or low bid, which is atypical for public K12 districts. Two have used the alternative delivery method, Construction Manager at Risk, and James W. Rice Elementary School is using a Qualified Bidders List. Statements of qualifications were due 11/27/18.

| Project | Design Firm | Design Fee | General Contractor | Delivery Method | Initial Construction Value |

| ATS | ADM Group, Inc. | $137,020 | Ry-Tan | CMAR | $2,629,721 |

| Cordova | ADM Group, Inc. | $105,400 | GCON, Inc. | Low Bid | $1,996,828 |

| Carol Peck | ADM Group, Inc. | $105,400 | GCON, Inc. | Low Bid | $1,998,450 |

| Madrid | ADM Group, Inc. | $195,000 | Chasse Building Team | CMAR | $3,675,900 |

Inefficiency of Design Services Contract

Ten of the individual projects are functionally identical gymnasium buildings on 10 different campuses. The Architecture firm is under contract to be paid a full design fee, even though nine of the gyms will repeat the design work already completed for the initial prototype.

Ten identical projects… No new schematic drawings… Very little design development and construction document work after the initial prototype… Accounting for minor site modifications, such as changing colors to match the individual campus color scheme or moving a door location, the design firm will be paid nine more times.

Certainly there are costs the design firm will incur such as Construction Administration & Inspection fees; however, any efficiency is completely lost when paying the full design fee nine more times as if each building were being designed without an initial prototype to start with.

The concept of a prototype design repeated many times is uncommon on the public side. A local example wasn’t available to compare against.

What we can find is the private side using this model. Consider every Starbucks and chain restaurant and retail operation in the market. They realize efficiency of design, consistency of brand and commonality of look and feel by using design and construction methods that repeat.

We interviewed several individuals for background about this story, from one of the world’s largest retailers to national restaurant chains to automobile service stations. Konrad Harris, VP of Construction and Facilities with Panera Bread told us, “Everybody uses prototypes. From the 18 years I spent at Starbucks expanding their footprint to McDonald’s, everyone uses a few prototypes.”

Harris went on to describe how he would realize efficiencies of 40-50 percent in the design fees if he didn’t have to “reinvent the wheel”. He said that by no means are future projects “free,” but if all other considerations are the same — market location, permit requirements, etc. — the savings are significant under this model.

In a written response to emailed questions, a representative of ADM Group, Inc. defended the scope of work and full design fee, stating, “Preparing young minds in an educational environment requires a substantially different set of skills than preparing duplicative plans for chain restaurants and retail operations. Our K12 designs incorporate specific techniques to enhance learning and improve a child’s educational experience, making these projects substantively different from restaurant or retail.”

Additionally, the firm’s representative contradicted the district’s on the record statements to AZBEX about the prototype concept, stating their conversations with Stratman have resulted in the direction for four different models, and the complexities of the projects merit an even higher design fee than what the contract provides for.

This deserves examination. Below are floor plans presented to the Governing Board for three gymnasium projects: Alhambra Traditional School, Carol G. Peck and Cordova. The floorplates are nearly identical, and it takes a keen eye to spot any differences beyond updating individual school colors, mascots and modifying the entrance locations. It appears they have only minor differences that are immaterial.

Consider the complexity of the project: Concrete slab-on-grade, masonry walls, wood gymnasium flooring, bleachers, common mechanical/electrical/plumbing, and standard restroom details are not intricate or overly detailed, nor should they be for this application.

Since these gymnasium buildings are not used for classroom-style instruction, the statement of enhancing a student’s learning experience does not appear relevant. In our consideration of all projects across the state, these structures are nearly as simple as we can find. The complexity of construction arises from the constraints of working on an occupied campus, not the design details in this case.

Working on an occupied campus is commonly brought up as a barrier to entry for public K12 construction, despite the fact that occupied spaces are constantly renovated by competent contractors in other sectors. For comparison, renovating or expanding an occupied hospital brings forth highly specialized requirements for patient privacy (HIPPA) and infection control measures (ICRA).

Even using a retail operation as a point of comparison, critical systems of data transfer and the potential liability for merchandise damage and theft are considerations not seen on or providing comparable risks in construction of a new 10KSF building on an accessible site.

Restaurants have additional kitchen requirements with specialized fire suppression systems, more advanced MEP requirements to supply bar areas, higher degrees of finish materials and fixed furniture that demands more coordination with interior design teams.

Yet restaurant and retail operations across Arizona and around the world are able to realize significant savings in design fees. Why should a public school district not push for a similar favorable contract? When presented with and asked about these points, Alhambra did not respond.

From the monthly pay applications, we can identify patterns and approximate values for the typical gym projects. Roughly 10 percent will go to schematic design, 20 percent to design development, 45 percent to construction documents, and 25 percent to Construction Administration & Inspection. Certainly, the CA&I is appropriate, but the remaining 75 percent could have been negotiated when the work is so duplicative in nature. The total fees for Schematic Design through Construction Documents across all nine gyms is estimated at more than $750,000.00.

Construction Contracts

The construction market in Arizona is approaching cycle highs; many firms are seeing record-setting revenue. Fewer firms are aggressively pursuing work. Most are being increasingly selective on what projects they pursue while construction costs are rising.

Part of our conversation with Panera Bread’s Konrad Harris included the most efficient way to procure construction services. He described a method of purchasing the whole batch at once. For example, if he had seven stores to build in a market, he might bid one, then negotiate for the additional six with the successful bidder of the first.

That way, according to Harris, quality stays high because contractors don’t want to burn a relationship where they know more work is coming. He also lamented that given the current state of the construction market, his biggest challenge is getting manpower for projects. By arranging a larger quantity of units, he can secure a crew to build all of them and ensure they will get them done instead of losing the crews to a different project, not to mention the economies of scale seen from purchasing larger quantities of building products all at once.

That methodology of contracting for all the units in one fell swoop was echoed across multiple General Contractors we spoke with for background about this story. When presented with the scenario, they all described efficiencies in materials purchases, construction schedule and management staff.

Once again, AZBEX presented Alhambra staff with these points of concern, asking if that style of contracting was considered? Did any consultants help plan out the progression of the bond projects? Was any outside expertise brought in to make recommendations? Despite several days’ lead time and multiple requests, the district only responded that they were not willing to make any comments regarding the cost of any gymnasium project until construction is complete.

Marketplace Interest and Comparisons

In the November 30, 2018 issue of AZBEX, a low bid for a new highway came in $60M over the Engineer’s Estimate. One project. While that is an extreme dollar amount, the situation is not uncommon. Using an analysis of one month’s bid results compared to Engineer’s Estimates, a full 2/3 of individual bids came in at or over the estimated amount.

Contrast that with the recent experiences of Alhambra: Carol G Peck and Cordova were contracted using the traditional design-bid-build or low bid method. The market overwhelmingly responded – 13 and 12 bid proposals, respectively, ranging in price from just less than $2M to just less than $3M.

Two gymnasium projects were also contracted using the CMAR delivery method. Nine written statements of qualifications were submitted for each, and through a two-step procurement process, RyTan and Chasse Building Team were selected. Construction contracts were entered into for $2.7M and $3.6M respectively. The Madrid project using Chasse Building Team is the only gym project that has additional scope — two classrooms and significant site work.

The response from the market on the low bid opportunities is significant to say the least. The market aggressively pursued these contracts, knowing that a low bid procurement was a rare chance to enter a space typically dominated by a very small number of contractors.

Initial Contracts Show Massive Savings with Low Bid

Remove the Madrid project from consideration for just a moment — there are three identical gym buildings (see floorplans above), two low bid, one CMAR.

The initial CMAR contract is $700K more than the two low bid contracts. Projecting out to the end of the project, one would reasonably assume that the CMAR contract price is more likely to go down while the low bid contracts would go higher. That makes sense — the CMAR projects are open book, or, as the AIA contract 133 language describes, “The cost of the work plus a fee with a Guaranteed Maximum Price.”

Once every cost is documented, unspent funds get returned to the Owner. Low bid projects inherently include more risk of change orders driving the final cost of the project up instead of down. There is zero chance for any savings to be returned to the owner. There is also very little chance the $700K difference can be overcome and the CMAR contract ends up costing less than either low bid project.

Considering these projects are functionally identical — same market conditions, same design and same location/permit requirements — once construction is complete, we can and will compare the cost of the two delivery methods.

Lack of Due Diligence, Oversight and Transparency

Knowing that the low bid contract is starting out $700K lower than the negotiated CMAR contract for the same building, we would have expected Alhambra to continue to use low bid on future procurements. That is not the case. The most recent procurement — a new gymnasium for James W. Rice — is using a Select Qualified Bidders List.

We would have expected to see Alhambra oversee competitive subcontractor bids on every trade, at a minimum ensuring good value on the overall project cost by ensuring a component of price competition for individual trades.

We would have expected to see owner-approved subcontractor bid lists, open book documentation through monthly pay applications with invoices, conditional lien releases for every subcontractor, backup and documentation for every line item of overhead, General Conditions, and General Requirements on the invoice if in the Owner agreement.

In a written response to emailed questions regarding whether subcontractors were selected with a competitive price component, Barry Chasse, president of Chasse Building Team stated, “YES, BY CURRENT LAW, qualifications AND price are required to be considered as part of award of subcontractors. Chasse considers price, scope, schedule capacity, financial capacity, manpower availability, safety, quality and ability to serve on an occupied campus as part of our process.”

The statement of the current law requiring a competitive bid process for subcontractors on a CMAR project does not match the state procurement code for APDM: ARS 41-2578.C.2.e.ii. “requires subcontractors to be selected based on qualifications alone or on a combination of qualifications and price and not based on price alone.”(emphasis added)

In our opinion, this does not align with best practices we often hear touted across the public construction sector – more commonly we hear statements such as ‘open book is open book’, or ‘everything has to have documentation on a CMAR’. For comparison, Michelle Hamilton, director of purchasing for Mesa Public Schools, described a very involved process where the district staff is present and involved in every decision.

MPS does rely on the expertise of the contractors and consultants they hire, but the district takes full fiduciary responsibility for taxpayer funds. It was an alien notion to her that a district would not be closely involved in the oversight of a CMAR project, even stating, “MPS was always part of the selection process and part of the evaluation of the sub bids. While the CMAR is responsible for the bids from the subcontractor, the owner needs to be part of that process to discuss quality and standards that the district determines is beneficial to the district.

“The value in CMAR compared to the low bid method is in reducing costly change orders, providing higher quality projects and building collaborative members of a team. There has to be constant oversight of the project to ensure that taxpayers are getting a good value. I believe the benefit of CMAR is long term quality because you aren’t limited by the lowest priced products.”

We requested to sit down with not only Jeff Stratman, but also Superintendent Mark Yslas, and Communications Director Linda Jeffries to proactively discuss our concerns with the

documents we reviewed to ensure we did not misunderstand or misconstrue any details or come to any inaccurate conclusions. That request was declined; however, Stratman did initially state that they would answer written questions by email.

We requested information on due diligence processes, subcontractor bid oversight, and the apparent inefficiencies in the design services contract. No response was received despite multiple follow up requests.

We requested subcontractor bid information from Chasse and Ry-Tan, but received either no response or a polite decline stating that proprietary information is not open to the public, but open only to the Owner upon request.

We asked Alhambra if they inspected the books. They did not. Stratman dismissed the question as a ‘means and methods of construction’.

It is not.

Oversight of an open-book CMAR contract means there are checks and balances. The contract value is the cost of the work plus a negotiated fee. The cost of the work should be documented in spades, bulletproof to any public inspection, and defensible to any inquiry — whether it be from nosy reporters, governing boards, auditors, or anyone else — such as a parent or taxpayer ultimately paying the bills for projects in one of the state’s least wealthy districts.

2 Comments

An excellent, well researched, documented and written article. I certainly hope it gets the attention it deserves. Great job!!

WHAT DID YOU EXPECT. IT’S ONLY TAX MONEY!