By Roland Murphy for AZBEX BEXclusive

There’s nothing fast, cheap or easy about bringing a development project from concept to completion. From choosing a site, to designing to project, assembling a development team, procuring approvals and permits, assembling financing, et cetera, there are countless challenges and speed bumps to delay progress and add to costs before the build team turns the first shovel of dirt.

It’s understandable and accepted that owners, particularly small owners who aren’t major developers and don’t build strings of projects across the country, may try to save money and keep upfront costs to a minimum by keeping the development team small and not filling some positions that may be seen as “optional.”

While we haven’t performed an actual analysis, we’ve recently seen what appears to be an increase in the number of projects entering the submittal and land use/zoning approval process without an attorney representing the project before the various councils and commissions.

It’s understandable. Attorneys are expensive. If a project looks like a good fit for the site and community—and developers always think it does—why not save a few bucks and have the architect or engineer handle the submittals and navigate the process? After all they and other team members natively understand the design components and project goals. It should be fairly straightforward, right?

Wrong.

As skilled as an architecture or planning firm may be at recognizing needed project components and features, building codes and timelines, they are inherently less adept at understanding the legal, political, departmental and social climates that all come into play for zoning and land use issues. Those are associated skills, not core competencies.

Your endocrinologist may have done a great job getting your blood sugar under control. They probably also have a solid understanding of how the musculoskeletal system works. Even so, do you want them handling the surgery to place a plate in your broken ankle?

The unfortunate reality—particularly in the current climate of NIMBYism, development resistance and vocal opposition to even the most beneficial projects from some corners of the community—is that a project proposal can meet every requirement, “tick every box,” fill every imaginable best land use and still be arbitrarily rejected by city councils that are playing to the room and are standing for “preserving community character” above all other considerations.

In these situations—which are, unfortunately, tending toward the new normal—the chances of successfully navigating the approval process increase dramatically with the right guide.

Running ‘Horses for Courses’

We recently had the opportunity to speak with Adam Baugh, a partner at Withey Morris Baugh, about using an attorney versus tackling the process on one’s own.

As a partner in one of the state’s leading land use law firms, Baugh has an obvious bias. He and his team, however, also have decades of firsthand experience and have watched countless proposals encounter complications, many of which an experienced navigator might have foreseen and avoided, or at least prepared for.

Baugh said he often encounters cases where the owner starts the process and then runs into trouble, going so far as to have the requests rejected and having to start over. “It happens a lot where someone will take the application, it’ll get denied and now they have to go to council and they’re in a bad spot with a case that should otherwise get approved.”

Speaking about those types of cases, Baugh said, “They might think they’re saving money or that they can do it, and I don’t have issues with that. What they don’t realize is there are real consequences at play that will cost them more money, take longer, cost them more political capital, likely affect their site plan more than what they were intending to develop, and at the end of the day possibly even cost them their financing if it takes longer to get done.

“I think they think they’re saving money by having a do-it-yourself case and not hiring counsel from the beginning. That often costs much more in the long run.”

As with any other component of the development process, Baugh said it is necessary to hire the right skill set for the various particular tasks. “You really don’t know the true prospects for your case. The thing that we do well, because we do this day in and day out, is provide more predictability in what is an otherwise uncertain process. There’s no guarantee anybody will get their zoning case approved, so why risk going solo or hiring the wrong talent? That only amplifies the uncertainty when what you need is more predictability.”

He explained that success comes down to applying the correct specific experience, and a key component of that is knowing and having relationships with the specific players in a jurisdiction and knowing the particular nuances of that locality.

“You hire anyone because of their expertise in a narrow area,” Baugh said. “You wouldn’t hire me to go draw up a site plan. I might be able to get feedback on a plan someone showed to me, but that’s not where my core strengths are. Hiring an engineer is definitely one of the first things you need to do to design a plan, but he’s not going to be able to tell you what the tolerance with staff is to approve the intensity of this effort or project. I keep getting hired by people who don’t do this basic due diligence, so I know it’s getting overlooked. It happens weekly.”

Case Study 1: Ikonic

Having the right relationships in place and a thorough understanding of the process, procedures and guidelines relevant to a case are essential factors in getting cases approved, as is the ability and willingness to advise patience and a steadfast, step-by-step approach.

One case that represents these combined elements is the 2021 approval of the Ikonic multifamily development, currently in pre-construction at the SWC of Bell and Scottsdale roads in Phoenix. The plan from developer The Hampton Group initially proposed a 255-unit apartment building with a height of 141 feet. The unit count has since been revised down to 245. (AZBEX, Oct. 15, 2021)

For comparison, the Frank Lloyd Wright Spire across the street in Scottsdale is just 125 feet. Even though the City of Phoenix tends to view new development far more favorably than the City of Scottsdale, planning such a tall, dense development raised concerns in the surrounding area, in Phoenix’s Paradise Valley Village Planning Committee and all the way up the approval chain. Scottsdale residents and officials also repeatedly expressed their opposition.

Nick Wood of the law firm Snell & Wilmer was the lead attorney on that case. In an October 2021 interview, he shared with us the process that led to the project ultimately securing the necessary recommendations and approval.

The Hampton Group and the team understood the need for patience and incremental advancement of the plan. Wood and his staff prepared materials demonstrating the Ikonic proposal followed land use guidelines in both Phoenix and Scottsdale. The Phoenix General Plan recommends development, “Locate land uses with the greatest height and most intense uses within village cores, centers and corridors based on village character, land use needs and transportation system capacity.”

The Scottsdale & Bell project met all those guidelines, since it is just north of the dense retail and residential developments in Kierland that sit on both the Phoenix and Scottsdale sides of Scottsdale Road.

At that time, Scottsdale was only recently solidifying its shift to a generally anti-development, anti-density mindset. Even though Scottsdale had no direct say in the approval process, to mitigate opposition the land use team showed Scottsdale’s Greater Airpark Character Area Plan supported the development standards for Ikonic by mandating, “Landmark intersections are key junctions and should be framed by prominent landmarks and enhanced streetscape treatments.”

The team also undertook extensive research into the area’s traffic patterns and the impact of the proposed development.

Next, representatives launched a public outreach and education campaign to garner resident support and address as many specific concerns as possible.

The efforts required patience and consistency in execution. Rather than pushing for the usual two-to-three-month interval between an initial presentation to a village planning committee and a hearing, Ikonic took six months and used the time for outreach to community members and City staff, making changes to the proposal and answering questions in advance of the official action.

By the time the requests came back before the Committee, communications about the project totaled 21 statements of concern and 169 statements of support, with no one speaking out in opposition at the hearing.

Case Study 2: The Score at Cottonfields

Baugh had a more recent case he used as an example of the patience and relationship management needed to move a complicated proposal forward.

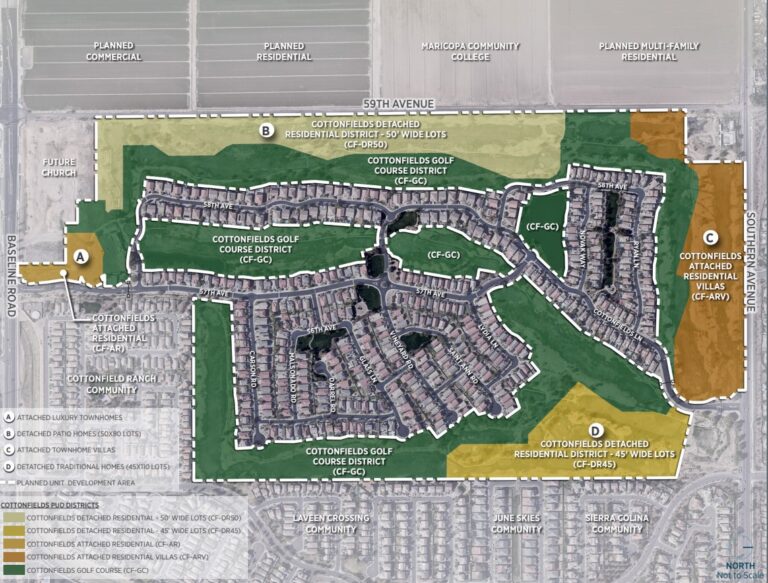

Property owner Alan Robinson and his company Laveen 140 LLC want to build a housing development on the site of the abandoned Bougainvillea and Southern Ridge golf course at 59th and Southern avenues.

The original plan called for 800 homes built around a 90-acre park, according to news reports. Unfortunately, surrounding homeowners were initially aghast at the idea and wanted the golf course reactivated instead. A similar case in Ahwatukee dragged on for years after starting as far back as 2014, with the potential developer ultimately being forced to abandon the housing plan and restore the course.

For the Laveen 140 development, there were approximately 450 surrounding homeowners to sway. Those residents had more than the power of their voices to present in opposition—they had legally binding covenant, condition and restriction agreements in place detailing acceptable uses for the property.

“You have not only the Councilmembers to try to persuade,” Baugh said in our interview. “You have to convince two-thirds of the 450 surrounding homeowners to amend their CC&Rs.” At least four other redevelopment proposals had been brought forth previously and had failed.

Baugh and his land use team worked for two years to adapt the plan and work with community members to shift opposition into support. “Can I bring forth a rezoning case and get it approved?” Baugh asked. “Yeah, I probably can, but without the CC&R amendments, a rezoning is worthless. It doesn’t matter what the rezoning allows. So, creating a strategy that involves community engagement and meaningful participation is essential. We’ve done more than 30 large and small group neighborhood meetings. We hired a political consultant to run a neighborhood campaign to collect the signatures. We’ve worked on telling our story. We built a plan together with the neighbors so they agreed to the concepts and gave us direction. They agree to the evolution of the plan because now it’s their plan.

“We created the strategy, which took more than two years, and we’ve pulled off the unthinkable,” he continued. “We’ve gotten 300 homeowners to sign a consent to amend their CC&Rs. We’ve crossed the required threshold for amendments. We have a plan that meets all the neighbors’ expectations and criteria. Originally, we had 800 neighbors opposing; now we have eight neighbors opposing.”

Baugh submitted the revised planned unit development proposal for The Score at Cottonfields last month. It is scheduled to go before the Laveen Village Planning Committee over the summer and will probably go to Phoenix City Council in September.

The submitted draft calls for 415 owner-occupied single-family houses and townhomes and a new 20-hole golf course with a clubhouse and other amenities, which the developer will start building as a “good faith” gesture before the Council rezoning vote.

The Right Skills at the Right Time

One of the key challenges in getting projects approved is the arbitrary discretion given to oversight bodies. Unless a particular use is permitted by right in a plan’s existing land use, a council can deny a request even if it checks off all the legal and procedural requirement boxes.

Baugh compares navigating a proposal through the necessary channels to making a dessert. “To build that best cake, there are a lot of components that go with it: Salt, sugar, baking soda, flour, eggs, what have you. The thing about a case where there are discretionary approvals is you really have to figure out what are all the necessary ingredients that are going to be required to overcome neighbors but also to overcome subjective discretionary issues.”

He continued, “Where zoning attorneys really excel is in building the recipe and assembling the ingredients. It might be the right traffic engineer. It might be a traffic study. It could be an economic impact study. It could be a crime analysis. It could be the world’s best architecture and design.

“Sometimes you have to get very creative. I recently had a case that had significant neighbor opposition, but I had to figure out what the city was most mindful of. It turned out the city was mostly concerned about water. In talking with our users, we found a way to reduce use by almost a million gallons of water per day.

Baugh went on to say, “When you’re creating the recipe and assembling the ingredients, understanding what are the key points for the councilmembers and building the recipe for addressing those key points is what we’re really good at. I think the key difference between a land use attorney and, say, a planner or an architect is they usually haven’t been tested as much in the face of the fire to have to solve all those random little items that are necessary to get everything across the line.”

After providing several examples of other cases involving finding solutions to various councilmembers’ concerns about different projects, including issues involving potential property tax offsets, employment opportunities generated by uses, water management and others, Baugh concluded by saying, “When you cut through everything, the biggest benefit we provide, or that a land use attorney provides in general, is a depth of experience, a history of relationships and the fact that we’ve probably seen and solved any problem that can come up. Ultimately, it’s a depth of applied knowledge versus theoretical.”