By Roland Murphy for AZBEX – BEXCLUSIVE

There was a bevy of housing and housing construction-related news in my inbox this week. There always is, of course, but lots of this week’s messages had actual data instead of just the usual handwringing.

Since Housing makes up more than 27% of the Arizona construction market, we felt a recap and scanning of the lay of the land might be in order.

Supply and Demand Balancing

Let’s start by taking a look at multifamily rents at the end of February. According to the Yardi Matrix National Multifamily Report, rents increased by $1 to $1,713, marking the first increase in seven months. Single-family rents dipped $2 to $2,133 with year-over-year growth down 0.5%.

Since stability tends to frighten speculators, pause here for a breath. Yardi wastes no time getting to the drama, saying, “The stability on the surface belies a host of changing trends that are keys to determining the direction the market takes from here.”

Those trends, of course, have been much-discussed, particularly over the last two years. The key factor is the intersection of supply, demand, pipeline and existing inventory across all housing types. Yardi says, “Demand has remained healthy throughout the period that rents have been flat, as strong absorption was more than matched by an unusually high number of deliveries. The national occupancy of stabilized properties fell by 60 basis points year-over-year to 94.5% as of January, after peaking in late 2021 at 96.2%. Occupancy rates will likely slide further, particularly in markets with large numbers of units under construction, as we forecast 1 million units to come online through the end of 2025.”

Who would have imagined, five years ago, that 94.5% occupancy would be worrisome, rather than slightly to the low end of normal and healthy? For the first time in decades, enough units are being produced in a calendar year to meet a year’s worth of demand.

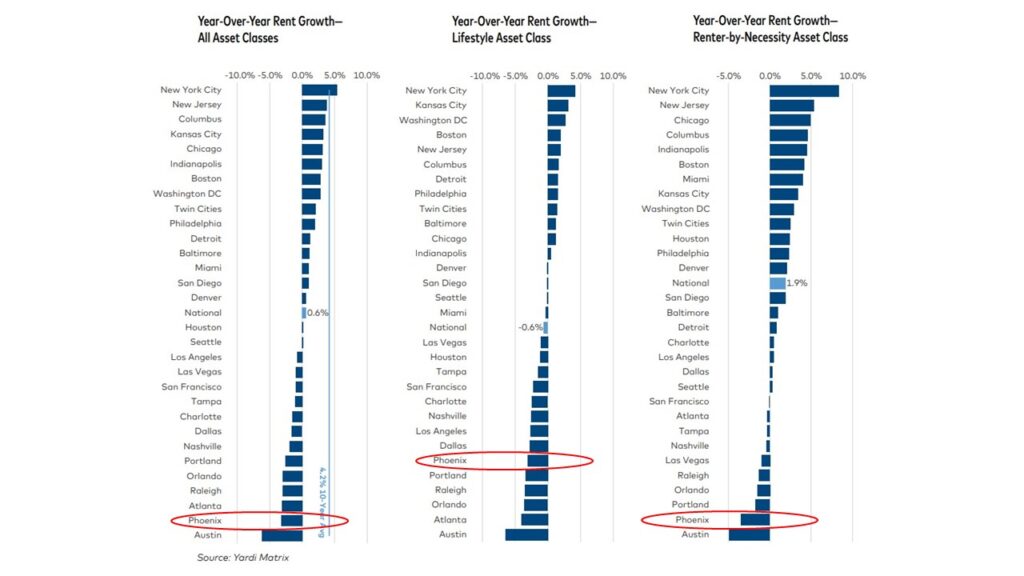

After leading the nation in rent increases—or rent inflation, depending on one’s position—the Valley is now one of the more rapidly cooling markets. Yardi’s news report shows Phoenix rents fell roughly 4% across asset classes in 2023, with similar results in both the Lifestyle Asset and Renter-by-Necessity classes.

Bear in mind, however, that retreat comes after increases of more than 30% and an on-a-dime market shift from one of the country’s more affordable to the least affordable metro areas.

Remember back in 2017 when market analysts freaked out about how badly we were underbuilding? That study reported a need for around 11,000 units per year in Phoenix through 2030 to meet demand, and that was before the pandemic and post-pandemic increases in in-migration and other economic development upticks.

That was just for multifamily. Subsequent research, including data from the Morrison Institute for Public Policy at Arizona State University, shows a shortage of 270,000 units across housing types.

While single-family is not one of our areas of regular focus, we can’t skip over it when talking about the overall housing market. One major reason for the surge in multifamily is the explosive increase in single-family homeownership costs, which was also fueled in large part by underbuilding.

Ariz. Among Least Affordable

According to a March 11 Arizona Republic article, Arizona is now ninth among the 10 least affordable states for home purchases. The article reports, “Only 22% of the homes sold in the Valley during 2023’s fourth quarter were affordable for households earning the area’s median income. That’s down from 25% during the third quarter and almost 63% in 2021.”

While hardly the most objective of sources, an email this week from Clever Real Estate raised a few eyebrows. Clever looked at home prices in the 50 most populous cities across the country. Between 2000 and 2023, home prices went up 165% at the median. In Phoenix, prices increased 205% during the study period, going from a 2000 price of $145,824 to a current price of $444,802.

The rest of the state mirrored Phoenix, rising 203%.

Clever’s research found that, since 1963, home prices are 23 times higher, while inflation is 10 times higher.

And yet there’s wailing in the streets in some sectors that two years’ worth of deliveries momentarily exceed demand.

Housing Starts Decline

Housing starts have decreased in Arizona for two years in a row, with year-over-year permitting activity down 4.5%. Single-unit permits dropped 7.7%. In total, 58,335 new permits were issued in 2023. The Phoenix-Mesa-Chandler market had a drop of 3.6%, while Tucson plummeted 8.4%.

Arizona is not an outlier in this instance. Nationally, developers started construction on 1,400,000 new homes last year, down 9% from 2022. Permit issuances fell in 266 of the 384 total metro markets tracked.

In a profound understatement, the AZ Big Media article linked above says, “This slowdown in Arizona housing permits hints at challenges for housing affordability and availability across the state.”

It’s easy to lay the blame at the feet of “greedy developers,” and far too many people take exactly that path of least resistance. The reality is far more complicated. We won’t beat the tired horse of current market factors influencing the downturn in the housing pipeline, but among the items to consider are:

- Ongoing inflation across the broader economy,

- Higher interest rates,

- Ongoing labor shortages and increased labor costs,

- Increasing conservatism among lenders,

- Changes in capital and reserve regulations,

- Increased exposure to commercial real estate risks and resulting risk aversion across sectors,

- Global and domestic political uncertainty, and

- Entrenched local resistance.

Even for those investors and developers who take a longer view (which, fortunately, is a wide swath of the market), moving forward with production under those conditions is challenging at best, impossible at worst. A wait-and-see attitude cannot be condemned, no matter how desperately we need new units added to the inventory.

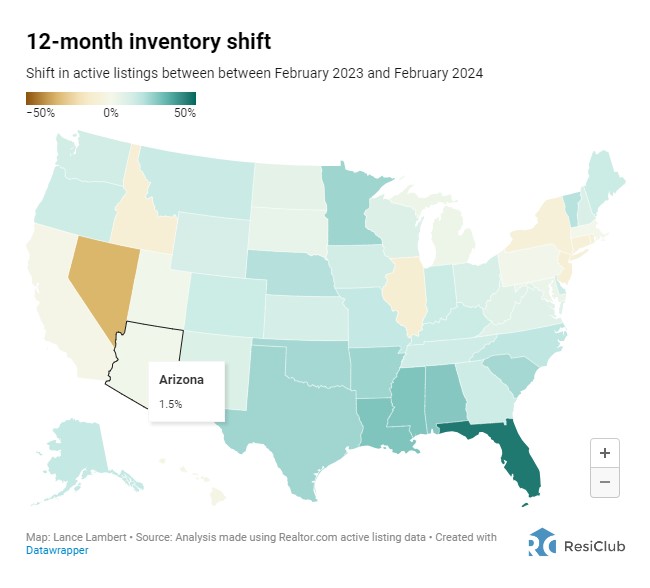

Speaking of inventory, another interesting item came in from ResiClub this week. The firm’s latest analysis shows, “The number of active U.S. homes for sale in February 2024 (664,716) is up +15% on a year-over-year basis from February 2023 (579,264). However, active inventory for sale is still down -40% from pre-pandemic February 2019 (1,102,660).”

It goes on to report that regional inventories vary widely. A look at the company’s state-by-state map bears that out. In Nevada (another recently frenzied boom market) active listings are down 32%. In Arizona, they are up 1.5%.

Addressing Resistance and Inaction

And now we come to that point in the housing column readers have come to expect: calling out local anti-development groups and the politicians who pander to them.

While not actually a majority in terms of actual numbers, the NIMBY brigades—particularly in more affluent communities—might as well be. They generally consist of wealthier retired or semi-retired residents who have enough money, free time and nostalgia for “the way things used to be” to sit through the five-hour-plus board and city council meetings to express their opposition to changing skylines, evolving local character and (though it’s rarely stated in public) the inclusion of “those people,” whoever “those people” might be in their eyes.

The real impact comes not just in the attendance at meetings, but in the turnout at the polls. Nearly every study on voter dynamics in local elections, including information from the nonpartisan voter engagement group FairVote, finds white, older, wealthier residents more likely to cast ballots.

Actual street-level sentiment in favor of development and increased housing across all types could easily outnumber opposition several times over, but if those members of the public can’t or won’t go to the meetings, draft and sign petitions, or, most importantly, vote for commissioners and council members, they may as well not exist.

As a result, many cities continue to reject rezoning applications for developments that would be a net positive to the community at large. At the same time, they impose new regulatory guidelines and generally focus on the wants of those vocal minorities over the needs of the community as a whole.

For the last few years, legislators at the state level have tried to rein in local governments’ growing implacability in terms of new unit development. Legislation has been repeatedly introduced that would curtail cities’ ability to set standards. Originally, these bills were intended as warnings and as a mechanism to jumpstart conversation and compromise. The tone was, “If cities don’t sort this out for themselves, the Legislature will sort it out for them, and nobody will like the result.”

The downside of bluffing, however, is the loss of credibility when the bluff is called and there are no good cards in the hand. Every year, legislators threatened cities. Every year, cities and their supporting organizations, like the League of Arizona Cities and Towns, beat back the threats. The cities became emboldened, and resistance became more entrenched.

Bipartisan Bill Makes Inroads

Then, this year, a much more modest bill with fewer initial restrictions drew enough momentum to actually pass because of the worsening affordability crunch.

Both Republican and Democratic lawmakers perceived enough of a crisis that HB 2570 passed both houses and was sent to Gov. Katie Hobbs for her signature.

While far less drastic than previous bills, 2570 is not merely a symbolic measure. Cities with populations of 70,000 or more would see several restrictions, including:

- Minimum lot sizes would be set at 1,500 feet;

- Setbacks from the street would be capped at no more than 10 feet;

- Minimum distance between homes would be reduced to five feet at the backs or sides;

- Cities could not impose specific architectural, design or aesthetic requirements; and

- Developers could not be required by cities to institute homeowners associations in new developments.

Opposition groups like the Neighborhood Coalition of Greater Phoenix, which lobbies for the preservation of neighborhood character, have decried the measure, saying it would create “a mishmash” of construction and housing types in established neighborhoods.

The League of Arizona Cities and Towns, rather than rallying under its normal flag of defending local sovereignty and autonomy, has instead taken the stance that the bill does not guarantee any improvements to affordability, even though the key factor in affordability has been increased supply across the spectrum of types.

As of 8 a.m. on March 14th, Gov. Hobbs has not taken action on the bill, although she is under increasing pressure to do so. Her representatives have said she is studying the measure.

Hobbs’ periods of greatest activity tend to be on matters where there is nearly universal support or entrenched partisan division. HB 2570 is not nearly so black and white.

Hobbs has said she wants any action on the matter to have bipartisan support. The current bill does, but it is nowhere near universal. She has also said she believes local officials are often most aware and capable of addressing the needs of their constituents.

The matter has put Hobbs on the horns of a dilemma. Does she sign the bill and alienate municipal leaders, or does she veto it and give her opponents political fodder that she refused to act on housing affordability when given a bipartisan path to doing so?

Regardless of what happens this week or next, the average renter and homeowner, along with those who aspire to afford “average,” is in for a long wait before any real change filters down to the street level.