By Roland Murphy for AZBEX

Aberrations, bubbles and anomalies don’t last forever. After more than two years of frenzied activity, it appears market gravity may have finally begun to exert its inexorable pull on the U.S. and Arizona multifamily markets.

So, is the sky falling? Is this just a return to normal? Is it a combination of both or the entry into a whole new state of existence?

In this column, we’ll take a look at some of the data and try to clarify the miasma of disparate reports and opinions currently swirling around the market and give you our own best guesses.

Multifamily Demand Drops

Reporters and analysts live for change. There are few things more disheartening than reporting the status quo. Add to that the fact that bad news and surprising reports generate far more clicks and eyes on pages than good news, and you can expect to see an uptick in gleeful coverage of the latest multifamily data.

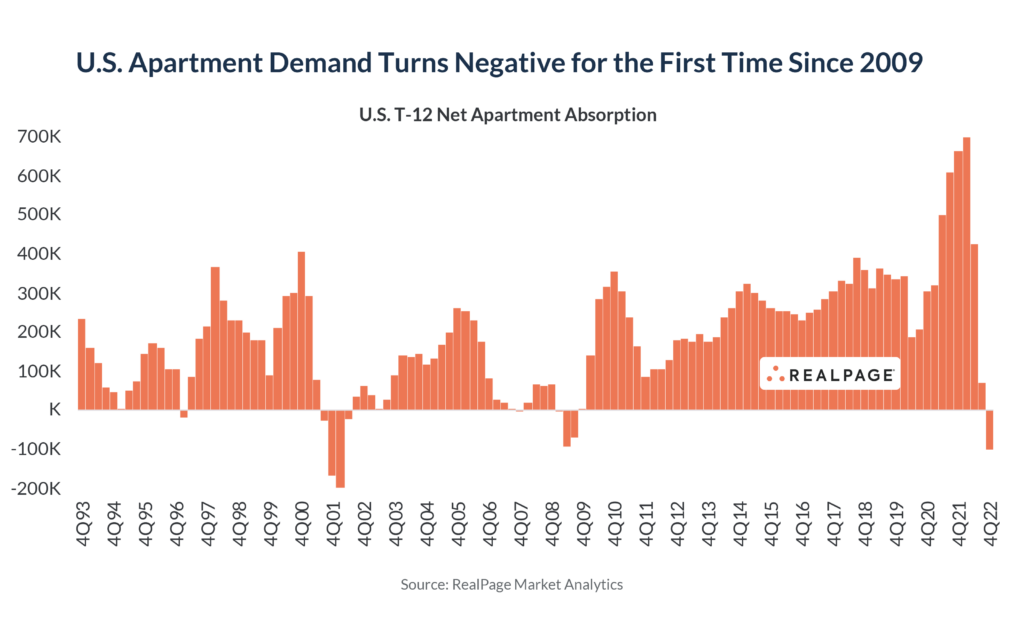

A Jan.5 report from RealPage SVP and Chief Economist Jay Parsons, ”Apartment Demand Turns Negative for the First Time Since 2009,” is the latest tale of woe to get tongues wagging and keyboards sparking, and with good reason.

After a massive surge in household formations and relocations post-pandemic, inflation and plunging consumer confidence weakened housing demand across every sector and type in 2022, even though wages increased and job growth was high.

The demand drop is primarily tied to the across the board decrease in consumer confidence. Even though inflation appears to have stopped climbing, it has yet to start falling to any significant degree. The Federal Reserve’s persistent program of interest rate increases may have had the desired effect of cooling inflation, but with many—perhaps even most—economists who make public statements saying some variation of, “It’s not if, but when,” a full-scale recession takes root, confidence fell more last year than during the Great Recession, according to research from the University of Michigan.

It is a popular misconception that when faced with risk people’s reflex is “fight or flight.” In reality, most people pivot to a rarely discussed third option: They freeze. Across markets and property classes, Americans chose to stay where they were in 2022. There was not even any perceptible summer “bounce” following graduation season when throngs of recently released students usually set out on their own and into new homes.

In the RealPage report, Parsons discussed 4 issues and trends commonly associated with weakening rental demand that are not in play this time around:

1. Large scale moveout/renter turnover.

2. Major increases in unpaid rent,

3. Renters “doubling up,” and

4. A “flight to affordability,” in which renters shift downward to less expensive apartments in their current city or move to less expensive markets somewhere else.

In response, Parsons said renter turnover is still historically low, 95.7% of market-rate rents were paid on time, the amount of doubling up is not significant, and renters are staying put.

Point Four, the “flight to affordability,” is particularly interesting and the trend of the last couple of years could easily explain why it didn’t happen. It could even be a primary contributor to the drop in demand.

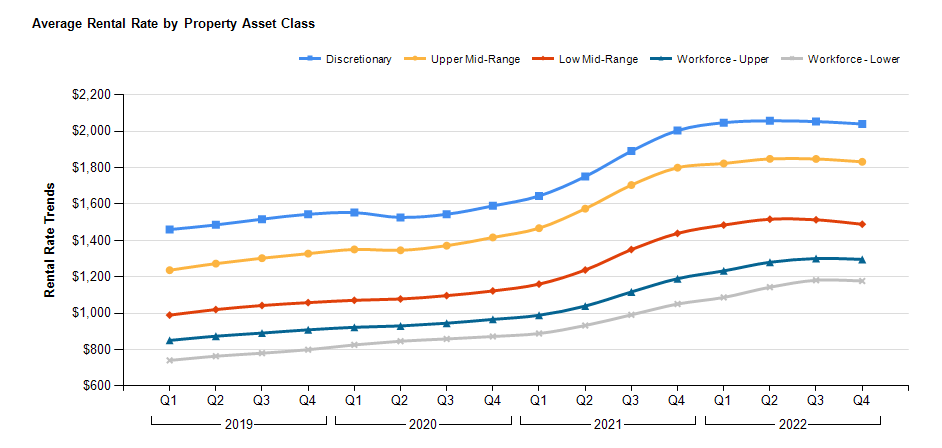

One factor Parsons did not mention, but that can’t really be argued, is there is no “affordable” left to “fly” to, at least not in any historically comparable sense. A renter would generally have to drop not one, but two asset classes to get any real savings.

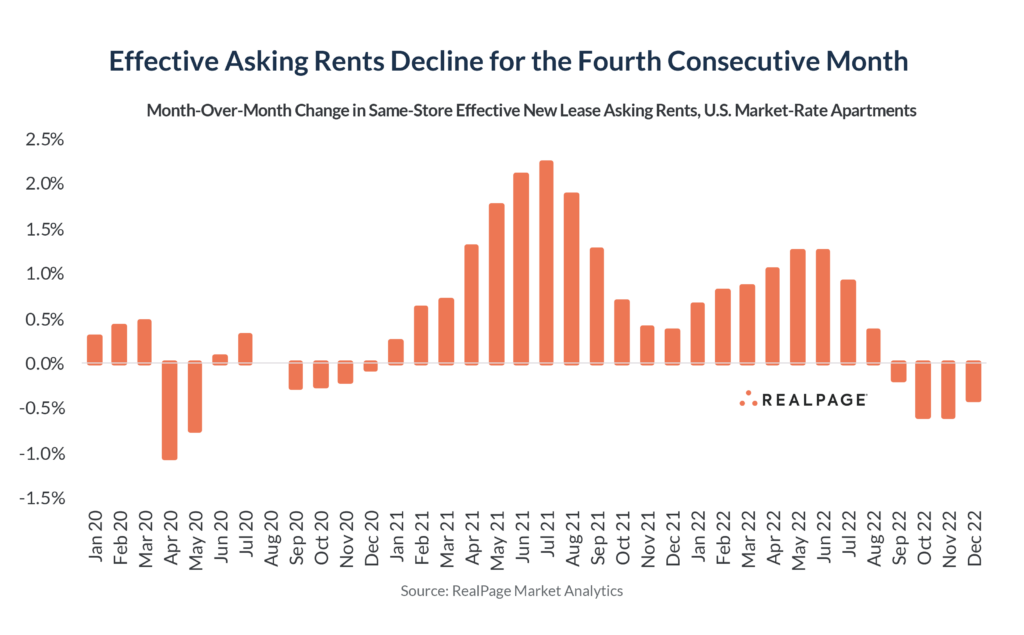

There’s another factor that is much more difficult to find qualitative data on, but which is a highly likely contributor: The renewal discount. Until Q3 2022 and much more so in Q4, rent increases were a given. However, the amount of increase was usually much less if renters stayed in their current unit than if they moved to a similarly sized unit in the same metropolitan area.

For example, say a couple rented an apartment in a top-tier “discretionary class” Phoenix community in Jan. 2020. They could have expected to pay $1,550 a month, according to Yardi Matrix. If their rent went up 6% when they renewed their lease in Jan. 2021, they would have been paying $1,643. If it had gone up another 10% at the start of 2022, the rent would have been $1,807.

Keep in mind, Phoenix was one of the leading, often the leading market for rent acceleration since 2018. Both in Phoenix and nationally, rents continued to go up through the first half of 2022 and only started falling in the second half. RealPage reports Phoenix rents fell 0.5% for the year.

Let’s assume our example couple did not see a change in rent for their 2023 lease renewal because the owner was worried about the decrease in demand, making existing tenants more valuable than ever. They would still be paying $1,807. But, rent increases are almost always higher for new tenants than renewing ones. Their same apartment, according to Yardi Matrix, was leasing at $2,040 at the end of 2022 for new tenants.

If they wanted to move to a new place and pay the same amount, they would have to go down a class. Upper Mid-Range in Phoenix was renting at $1,832 in Q4 2022. If, however, they wanted to realize any savings, they would have to go down two classes to Low Mid-Range, which was leasing at $1,489.

So, here are the choices our couple has:

- Move to a new place in the same class and pay $233 more;

- Stay in the home they’ve had for three years, know the neighborhood, have developed memories and attachments to, etc., and pay the same amount this year as last;

- Move to a less nice apartment, probably in a less nice neighborhood where they will have to learn the best routes, new grocery stores, restaurants, etc., all for the same rent they are paying today, or

- Move to a much worse apartment in a much worse neighborhood and actually realize some cost savings on rent.

Broken down by both cost and human factors, it’s not hard to see why many people may have stayed put.

Construction Impacts

It’s been about five-and-a-half years since the National Multifamily Housing Council and the National Apartment Association study that Phoenix would need 150,000 new multifamily units by 2030 to meet its housing needs. Given the faster-than-steady rate of in-migration Arizona and metro Phoenix has seen since then, that 12,000 units per year goal seems almost quaint.

What’s worse is that until the anomalous surge in rents, it had been unmet. As of last January, data from Yardi and ABI Multifamily showed Phoenix averaged 8,776 unit completions from 2017-2021.

Yardi Matrix data shows 12,559 units completed from Jan. 2022-2023. The market did lay on the spurs for 2021-2022, with a reported 22,673 completed.

A real problem for affordability, however, has been that more than 85% of units delivered have been in the top two asset classes, which, since the start of 2019, have seen monthly rents increase by more than $575.

So now we’re faced with two similar concepts that are operationally miles apart: The market needs tens of thousands of new units per year, but its demand is being constrained by the current, and likely worsening, economic circumstances at work now.

It takes a great deal of time and money to build a major construction project like a 100/200/300-unit-plus apartment complex, and both the time and money requirements have gotten larger in the last new years. It’s almost become like a sing-along to list the impacts of NIMBYs, drawn out approvals, design revisions, supply shortages, worker shortages, inputs cost increases, capital cost increases, etc. on project costs and timelines.

An equally large problem, however, is developer unwieldiness. It’s hard to get a company with a valuation in the hundreds of millions or low billions of dollars moving in the right direction at the right time. When you’re working with outside investor money, you’re forced to think in quarters or halves. Long view planning and action is not just discouraged, it’s impossible.

When capital was cheap and developments were leasing to capacity before construction was complete, it was easy to throw up as many projects as there were workers to build them. Now that full occupancy can be expected to take a couple of months, construction costs are higher and penciling out takes longer, investors and developers are getting nervous, and construction starts are slowing.

Yardi Matrix shows permit data for 69 Phoenix multifamily projects last year. Of those, 40 started in the first half and 29 in the second half. While 11 fewer projects starting in the second half might not make or break any market, and one data point is never a trend, it does reflect the activity level seen across most of the rest of the country.

Still, most major markets are on pace to meet or exceed record deliveries, which will add to investor worry and introduce even more caution into the market. It has to be realized, however, that while apartments may sit vacant longer, they are not going to sit vacant for any period of time that could rationally be considered “long”, given the need for units. Phoenix is currently at an occupancy rate of 94%. The renter volume is, in real terms, doing just fine.

There is good news and bad news for the market. Since lease-ups are going to take longer, owners will likely start offering incentives to counter the massive cost difference between where rents currently sit and what renters are willing and, more importantly, able to pay. While certainly not the frenzied fun of double digit rent gains, markets do better when there is a degree of stability and predictability, and cooling the market and lowering some prices to a more sane level will be good for everyone who didn’t overleverage thinking that degree of rent appreciation would go on forever.

The downside is that developers will almost certainly overcorrect in terms of project starts and new project planning. The biggest reason for the pent up need leading up to the current moment was that developers slammed on the brakes at the start of the Great Recession and then didn’t get back on the gas when they should have after the recovery started.

Had we, as a market and an industry, been delivering more than 8,000 units a year to a region that needed more than 12,000, then we, also as a market and an industry, would have been far better able to stabilize both through the peaks and the valleys of the last few years.

While the likelihood of the coming recession is hardly likely to resemble the Great Financial Crisis to any great degree, the likelihood of returning to the problems of underbuilding and unmet need cannot be so easily dismissed.

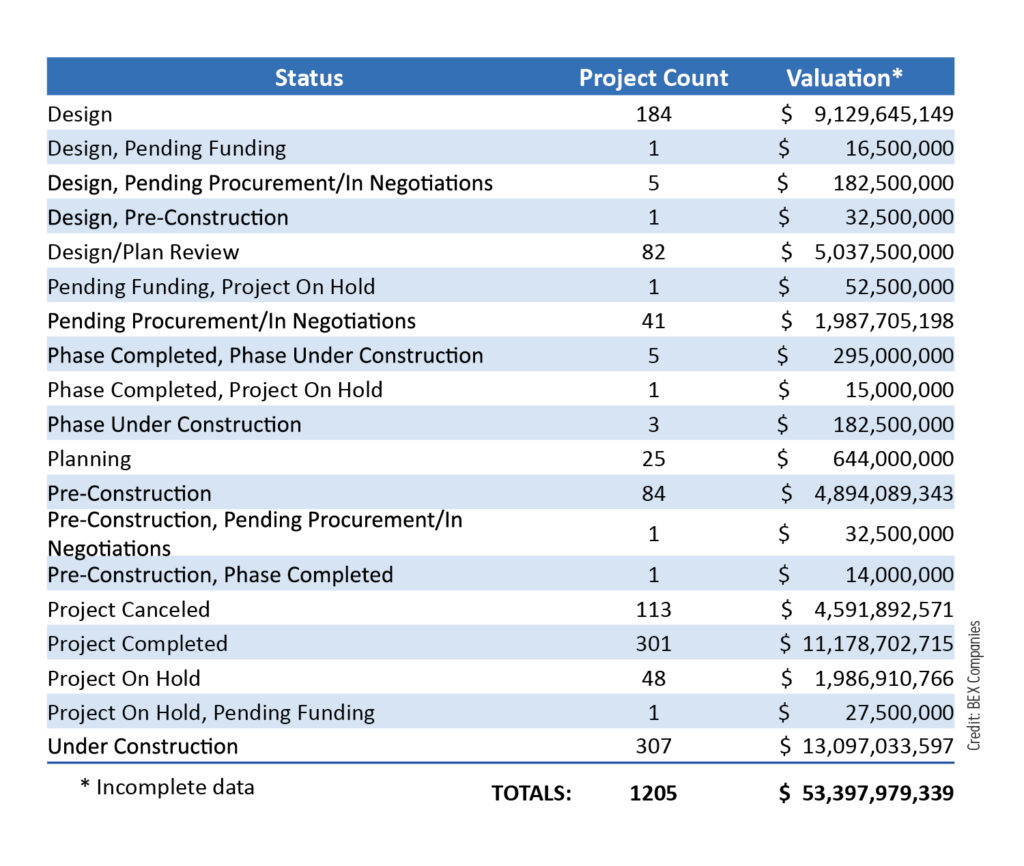

The DATABEX project database currently shows 435 multifamily projects in some form of design/planning/pre-construction, with a valuation of approximately $22.5B. Since 2016 113 have been canceled ($4.6B). Another 50 are on hold, for a total of $2B.

In that time, though, there have been 301 projects completed for a total valuation of $11.2B, and another 307 worth $13.1B are under construction.

The interesting item to watch over the next 12 months will be how many of those 435 design/planning/pre-construction projects move into the under construction column and which end up on hold or canceled.