By Roland Murphy for AZBEX

A foursome of experts from across the industry shared their thoughts and experiences on the current state of construction costs at the June BEX Companies Leading Market Series discussion this week.

Moderated remotely by BEX President and Founder Rebekah Morris, the in-person panel consisted of:

- Julian Anderson, president of Rider Levett Bucknall

- Chad Halmrast, director of preconstruction for TDI Industries;

- R.J. Radobenko, president of Global Roofing Southwest; and

- Blake Wells, VP of construction for LGE Design Build.

After presenting her standard market history overview, Morris gave the audience and panel a snapshot into the increase in entitlement and permitting lead times. For the one Valley city shown as an example, the process has gone from an average of four months before 2018 to 14 months today, a total increase of 180% since the pre-pandemic era.

The increase in timelines from submittal to permitting is significant because fluctuations in materials costs and availability vary wildly in the current market due to ongoing supply chain issues. The longer the process draws out, the less reliable cost and availability forecasting becomes.

Following her introduction, Morris turned to RLB’s Anderson for an overview of how Arizona construction costs have changed since January of 2020. He began by saying, “I think one of the things that people miss when they look at raw numbers… is that those are raw numbers. They’re today’s dollars compared with yesterday’s dollars.” He added this is an issue analysts have to consider. “What’s the correct inflator or deflator to use so we understand what the real volume is? Just because a number has doubled over 10 years or 20 years doesn’t mean the amount of work has doubled if costs have gone up 70%, for example.”

He then turned to looking at commodities like copper, lumber and oil as influencing factors in those cost increases. He pointed out the wild fluctuations make it difficult for the construction and development industries to estimate where any pricing will be at any particular time.

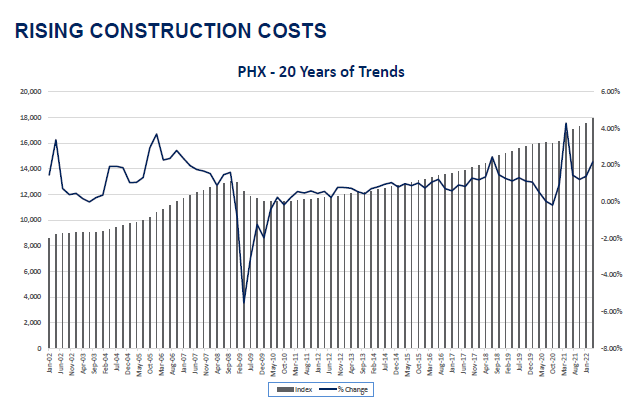

After introducing the concept, Anderson presented a slide showing RLB’s Phoenix bid price indexing over the last 20 years. Construction costs in the last 20 years have generally continued to increase, except for a slight dip from 2008-2010. “They just go up,” he said. “That’s what happens with construction costs.”

The slide, however, included an overlay showing the change in construction costs. Anderson pointed out and explained the more dramatic peaks and valleys in the chart – including the housing bust and the industry’s post-pandemic lockdown resurgence before turning to the most recent data.

“What we’re seeing in the last quarter is construction costs, as bid, have risen in the last quarter at an annualized rate of almost 9%,” he said. “What that tells me is that even though we have construction costs going up in terms of materials and other things, the bid prices are still being suppressed. When I say, ‘suppressed,’ people along the line are trying very hard not to pass on as much as they think they should be able to pass on. Pretty typical in a hot market like this.”

Turning to the other panelists, Morris asked them to summarize what they see as major cost increases in the current market. Wells said it largely depended on the project type. Industrial projects, he said, are getting hit particularly hard at the moment due to the high rate of demand and the supply pressures that puts on specific materials and inputs for those projects.

Radobenko said the key issue for his roofing and metal work is, “Today, we don’t know the price for anything that’s being delivered tomorrow. Everything is being priced on delivery. It’s hard for construction customers because we’re getting contracts farther out now and we have a longer lead time. Materials we order today, we get in six-to-eight months on the west coast. When you get east of Texas, it’s 12-to-18 months.”

He continued, “It’s really difficult to estimate. I have a lot of ‘I don’t knows.’ We price at today’s prices, and we just don’t know what going to happen in the near future.” He added another factor complicating business at the moment is warranty satisfaction. Given that warranties in roofing work can cover between 10 and 30 years, the ever-shifting ability to procure materials for warranty work makes both price estimating and work scheduling an ongoing challenge.

Morris next asked the panel to discuss and compare labor costs versus materials and other factors as a driver in increases. Halmrast said, “Looking at the impacts of labor versus material and equipment, I would say that materials and equipment are the biggest impact we have on costs right now. Yes, there is a war for labor and there are a lot of carrots being dangled right now, and there are a lot of ‘chasers’, but there are some that aren’t. I would say that of the total increase, about 30% is due to labor and the rest is materials and equipment.”

Radobenko echoed that finding and said his company had increased wages 20% across the board and only increased its labor pool by 2% because of the hyper-competitive market for talent.

Anderson explained labor and materials, while vital, are not the entirety of construction costs. “Below the line” items at the contractor and subcontractor levels – such as overhead and profit, contingency allowances, insurances, taxes, bonds, etc. – make up roughly 30% of costs. “That’s where some of the ‘squish’ is, where people are able to keep costs down by trying to reduce their overhead and profit and other things and causing some stress at some levels of the industry. It’s a real problem… especially when people were setting project budgets in 2018 or 2019 and had an expectation that that nice little flat spot of 3% or 4% increase was going to go on forever and then it didn’t.”

Regarding labor expenditures, Halmrast said there will always be “carrot chasers” who jump from one employer to the next in search of wage increases, particularly in the current market. He said TDI has found success in building relationships with employees who are more focused on finding a right fit culturally with the company and who consider their employment to be a long-term relationship of mutual value.

Radobenko said his company was compelled to raise wages across the board and used the need as an opportunity to reward and promote key employees to new titles and responsibilities to increase their investment in and attachment to the company.

Wells said LGE was compelled to increase compensation for both field and office-based staff because projects keep getting bigger and the need to attract and retain talent only increases.

In terms of attracting talent, Halmrast and Radobenko again reiterated the need to focus on culture, long-term employee/company relationships and other job satisfaction components in addition to financial compensation.

Moving the event toward its conclusion, Morris elicited chuckles from the panelists and the audience when she posed a question asking how much can we rely on predictions.

Anderson said the best guess is a minimum of 10% annualized rate increases until inflation gets under control. Wells demurred and said LGE’s predictions from January and February were irrelevant by May.

Later, Wells noted rent increases, particularly in industrial, have helped to absorb some of the cost increases, but that deal structures across the board are becoming more complicated. He said contracts are becoming more complicated to negotiate and that contingencies and pre-orders are much more important than ever before.

Radobenko and Halmrest said margins are down and continuing to fade, even though overall revenues are increasing due to costs.

Another chuckle came when Morris posed her closing question to Anderson to wrap up the event: What do you think it would take to pull construction pricing back in?

Anderson replied simply, “You don’t pull construction costs back in… What happens is the industry does one of two things: It grows or it slows, and if it slows the question is: How much does it slow” He added the two key influencers on how much slowing might take place are consumer confidence levels and the effectiveness and timing of Federal Reserve efforts to stabilize the economy.

“If that slows the economy and the industry, many of our supply chain issues will ameliorate and we’ll go back to something ‘normal,’ although we don’t seem, as an industry, to ever do anything normal. We either accelerate too fast or decelerate too quickly. It’s a question in my mind as to whether this next downturn is a moderate one or something different. We don’t, however, hold back costs.”